Generative Hierarchical Materials Search

The key idea

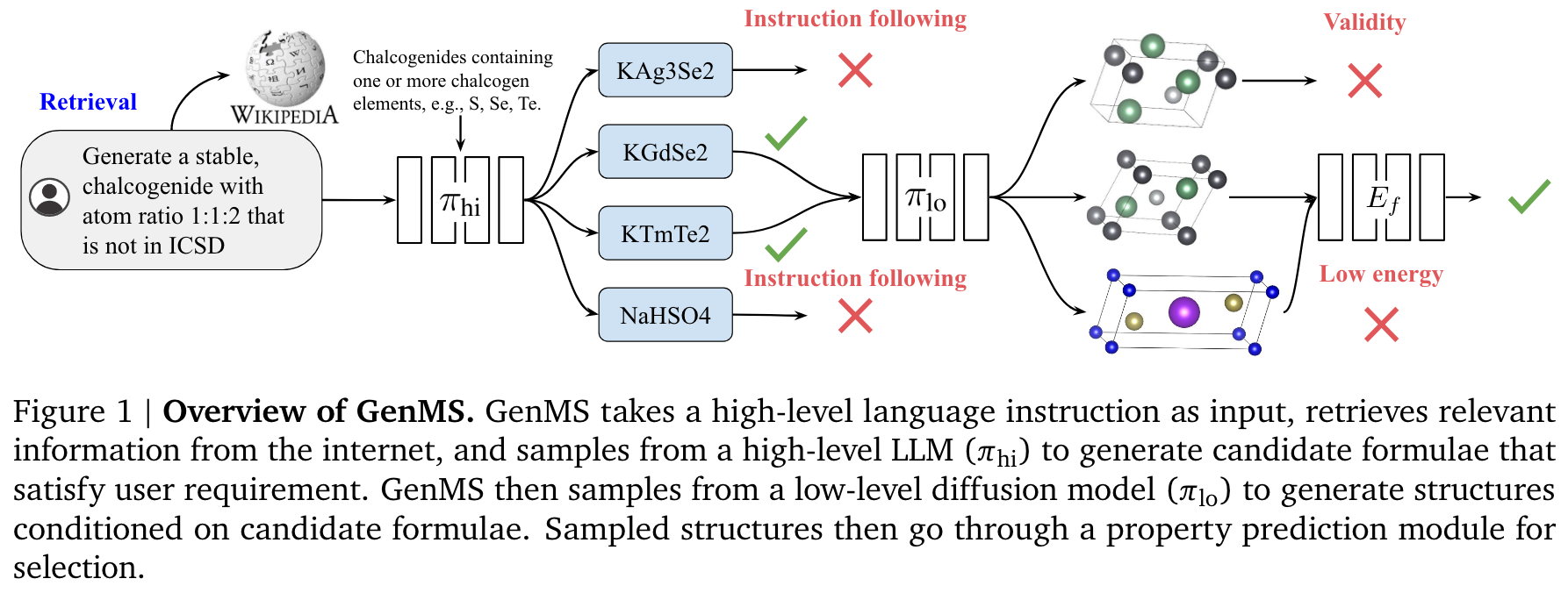

In recent years, machine learning based methods have increasingly been applied to assist the discovery of novel or improved materials with certain desired properties. In this paper, the authors present GenMS, an end-to-end generative model for crystal structures from language instructions. To that end, GenMS combines an LLM to process the user input, a diffusion model to generate molecular structures, and a GNN to predict the structures’ properties and select the best candidates.

Their method

The authors argue that data linking the properties of materials to their crystal structure exists at two different abstraction levels: high-level information is available as text, while lower-level structural information such as atom positions exists in crystal databases. To reflect this, the generative model is split into two components with the chemical formulae of candidate materials serving as intermediate representation:

- An LLM trained on materials science knowledge from sources such as textbooks is used to sample chemical formulae that satisfy the user’s directions. Retrieval augmentation is used to gain additional information and the formulae of crystals from existing databases are provided in the context to avoid generating known crystals.

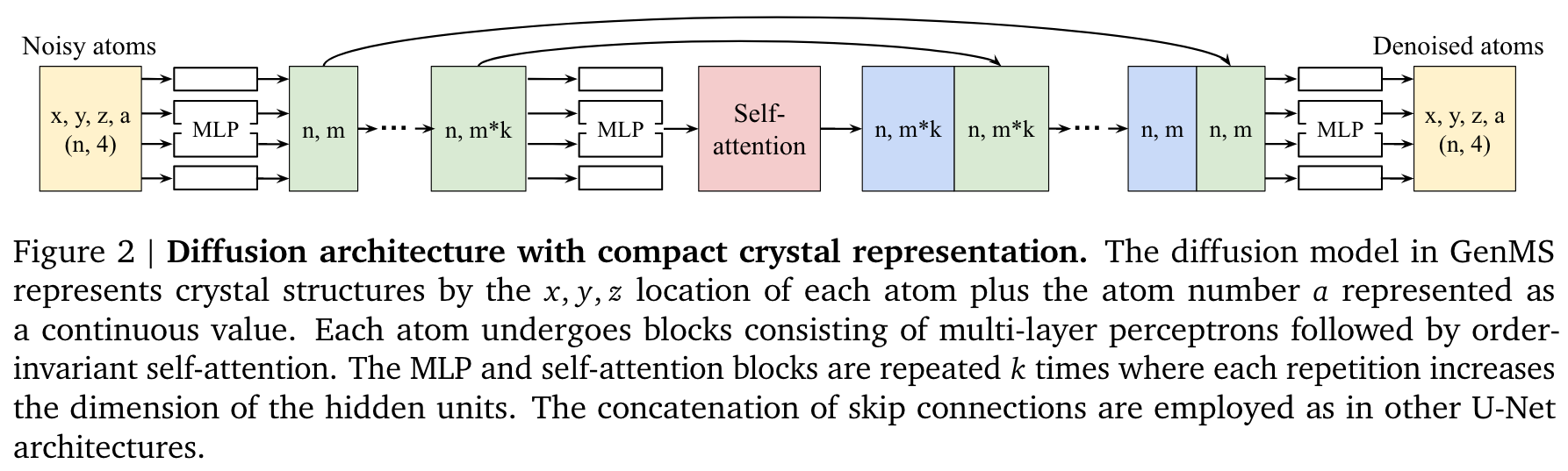

- A diffusion model trained on crystal structure databases then generates crystal structures from these formulae. To improve the efficiency of the diffusion model, a simple representation using the 3D position and atom number of each atom in the crystal is adopted instead of e.g. a graph.

As a final step, a pretrained GNN is used to predict the formation energy and potentially other properties of the generated crystal structures and rank them based on this result.

During inference, a tree search is performed to identify low-energy structures that satisfy the natural language instructions. Here, the number of generated intermediate chemical formulae and crystal structures are hyperparameters to trade off compute cost for result quality.

Results

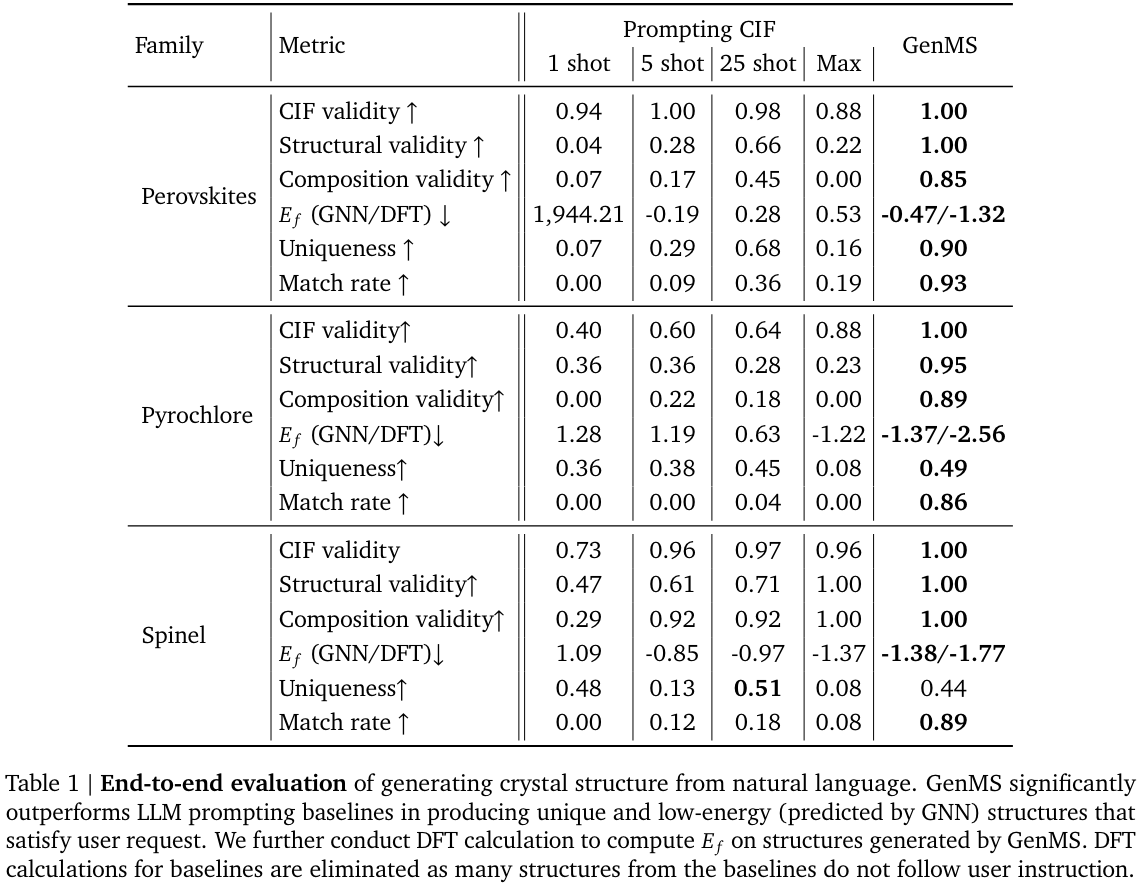

The main baseline presented in the study is an LLM that is prompted to directly, i.e. without the chemical formulae as an intermediate representation, generate crystal structures in the form of crystal information files. GenMS significantly improves on this baseline in all investigated quality criteria. Furthermore, the authors demonstrate that the model follows simple prompts such as requesting a metal or a material that is not present in a given list.

Takeaways

The possibility of sampling materials based on natural language instructions in an end-to-end fashion is a promising direction for improving materials generation and making it more accessible. However, the authors acknowledge a few shortcomings that require further work. In particular, more specific user input (e.g. “generate a semiconductor”), the generation of more complex crystal structures and the inclusion of further criteria such as synthesizability of the generated material remain challenging.

Comments