Beyond Chinchilla-Optimal: Accounting for Inference in Language Model Scaling Laws

The key idea

The authors modify the scaling laws from the Chinchilla paper to account for the additional cost of running inference on a model once it’s been trained. That’s the rationale behind models like Llama training on a huge number of tokens — this paper now provides a mathematical justification.

The key conclusion they draw from their analysis is:

LLM practitioners expecting significant demand (~$10^9$ inference requests) should train models substantially smaller and longer than Chinchilla-optimal.

Background

In 2020 OpenAI kicked off a trend of deriving so-called “scaling laws” for transformers, in their paper Scaling Laws for Neural Language Models. They identified a mathematical relationship between the pretraining loss and each of: model size, dataset size and amount of compute.

This was a highly influential paper; used to justify the size of their enormous 175B-parameter GPT-3 model and set a precedent that other 100B+ LLMs would follow in the next couple of years. Their conclusion:

optimally compute-efficient training involves training very large models on a relatively modest amount of data.

In 2022 DeepMind released their Chinchilla model, in a paper that revised OpenAI’s scaling laws, rightly suggesting you should train smaller models on more data than originally claimed.

But this wasn’t the end of the story. Meta’s recent Llama models are trained with an even lower params-to-tokens ratio than Chinchilla. Versus GPT-3, the smallest Llama 2 model uses 25x fewer parameters, but over 6x more data.

Why is this the case? Do we need yet another adjustment to our scaling laws?

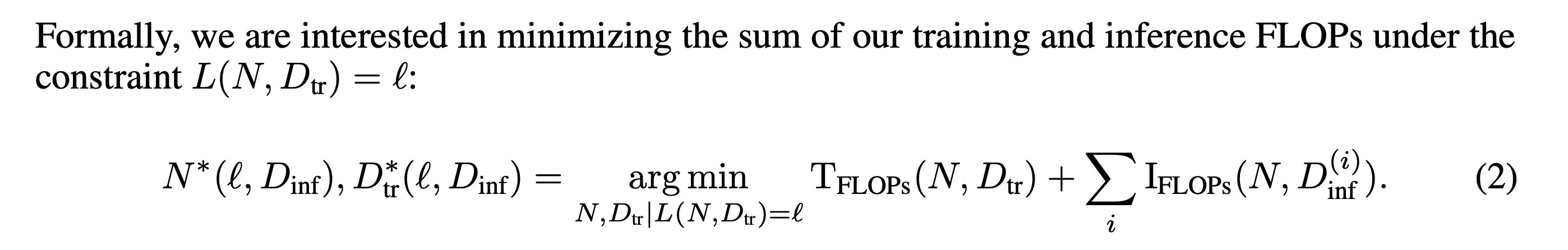

Their method

The problem the Llama designers are accounting for with their “over-trained” small models is that of inference costs. Practically speaking, it’s easier and cheaper to serve a small model than a large one.

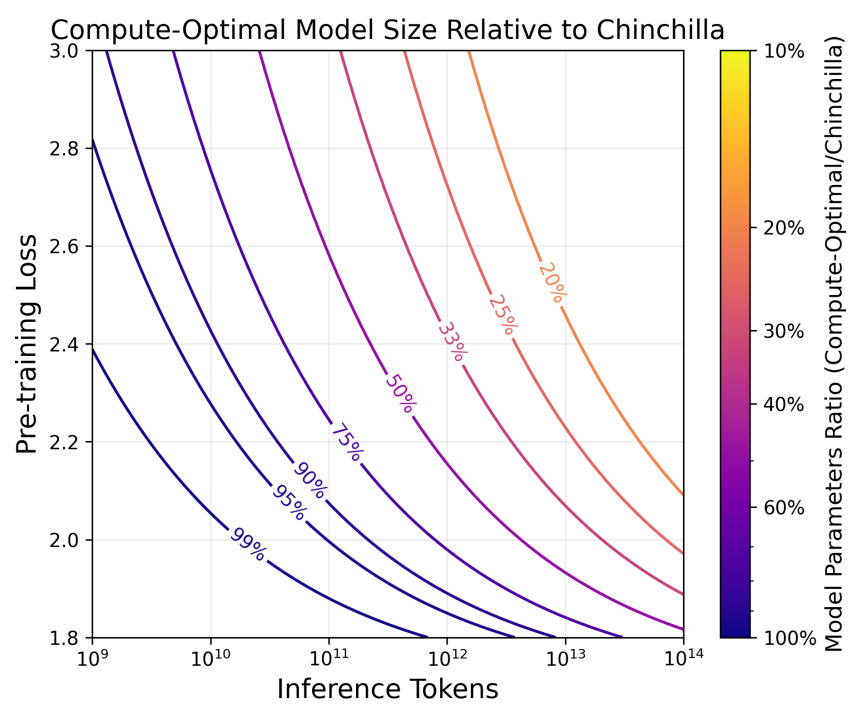

In this paper the authors modify the Chinchilla scaling laws to account for inference costs. Given an expected number of inference tokens and a target model quality (i.e. loss), their new compute-optimal formula states how many parameters and training tokens should be used.

Results

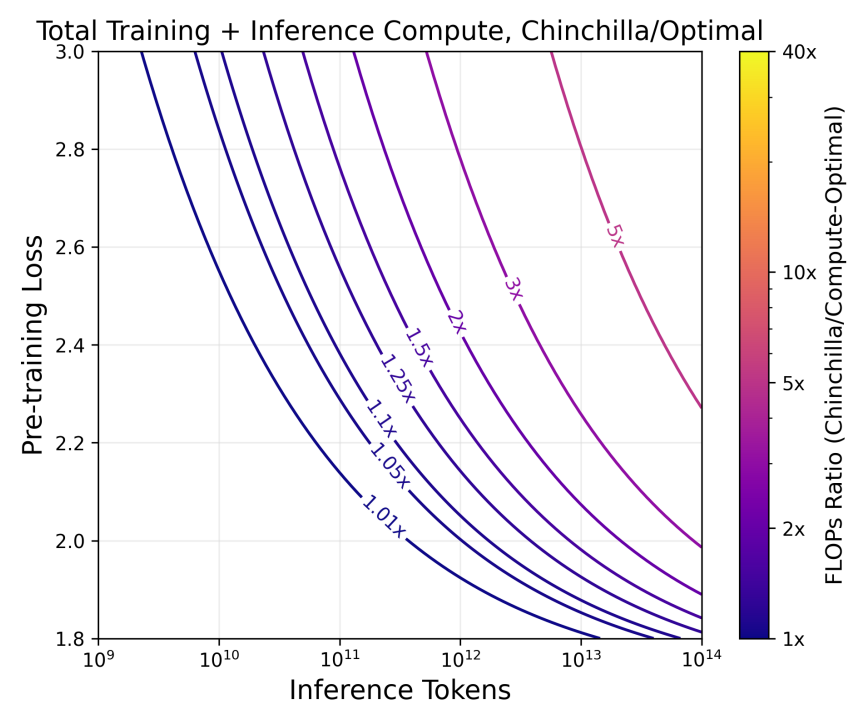

This formula reduces the total compute (training + inference) required, relative to the original Chinchilla rules:

This is an improvement, but there’s still a considerable gap between this and the “real world” costs of running such a model. The above doesn’t account for:

- Inference vs training hardware utilisation

- The ratio of prefill to generation for inference

- Quantisation for inference

- Different inference hardware

To address these points, the authors introduce a second cost-optimal formula, which accounts for the costs, hardware utilisation and number of tokens at different stages. This makes the model much more realistic and gets closer to the approach adopted by Llama.

Takeaways

Of course, one can never know ahead of time how many requests a model will be used for, so there are limits to this approach. It also doesn’t account for some practical benefits of smaller models (easier to fit on a single chip, lower latency). Nevertheless, this is still a much-improved model of the real-world costs of practical LLM use.

Comments