FP8-LM: Training FP8 Large Language Models

The key idea

The authors show that you can use FP8 weights, gradients, optimizer states and distributed training without loss of accuracy or new hyperparameters. This is great because it reduces the memory overhead of training, as well as the bandwidth costs.

They train up to 175B GPT models on H100s, with a 64% speed-up over BF16. Pretty impressive, and a bit faster than Nvidia’s Transformer Engine.

Background

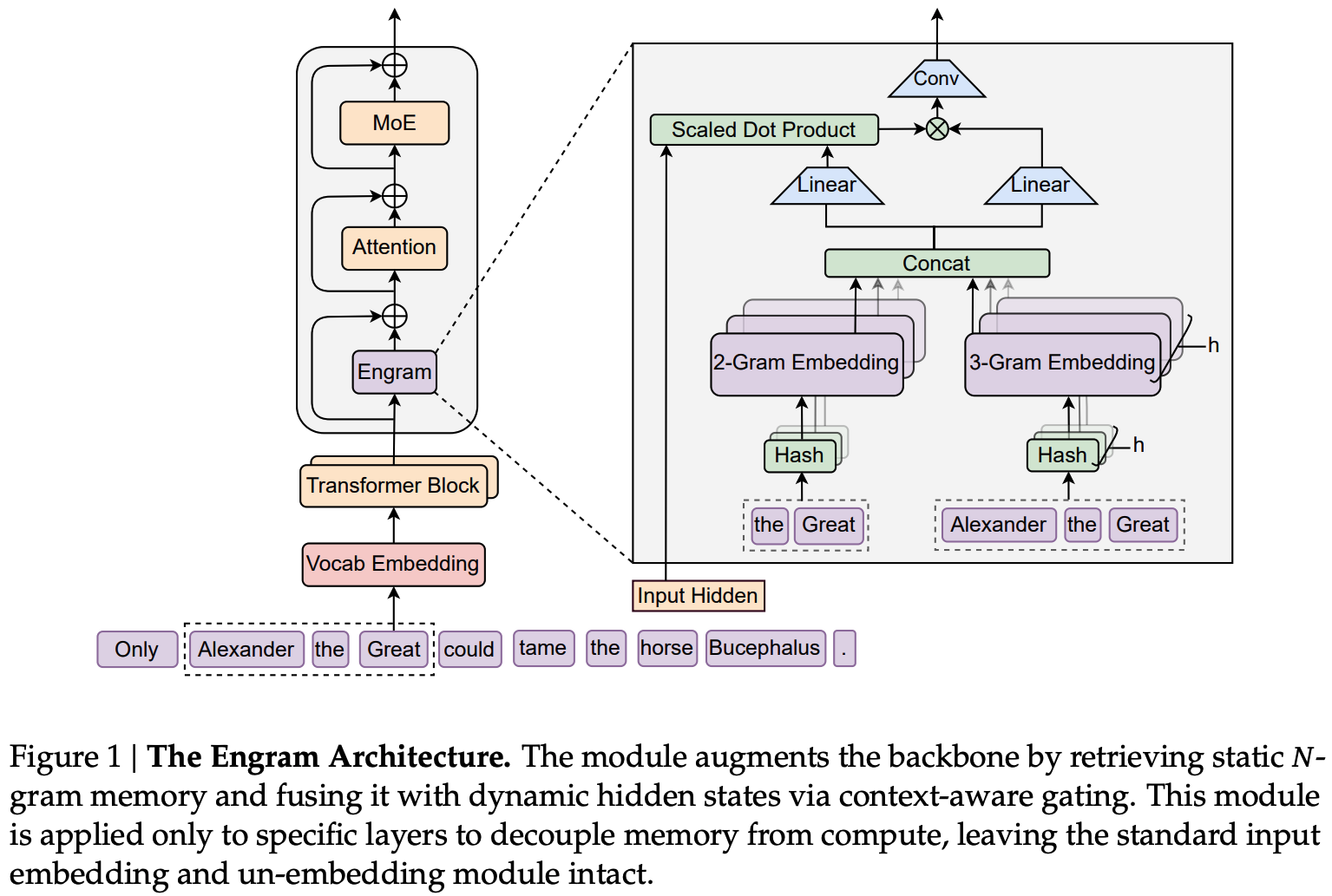

The fact that LLMs can be trained “in FP8” has been well established, but what does this mean? In reality, all FP8 training is mixed-precision as putting all tensors in FP8 degrades the model. The simplest and most common approach is just to cast linear layers to FP8, gaining the benefit of improved FLOP/s assuming you have hardware with accelerated FP8 arithmetic.

However this misses out on a second benefit - reduced memory and bandwidth costs if we can also store/load values in FP8. It’s less clear from previous literature what else you can put in FP8 without things degrading.

Their method

Gradients

The issue here is scaling the gradient all-reduce ($g = \sum_{i=0}^N g_i / N$) so it doesn’t overflow or underflow the narrow FP8 range. Two naïve approaches are to either apply the $1/N$ scaling to each individual $g_i$ before the reduction (risks underflow), or to the final $g$ afterwards (risks overflow).

They fix this by partially scaling before, and the rest after the all-reduce. The scaling factor used is determined empirically by gradually increasing the scale, but backing off on overflows.

Their FP8 tensors also have an associated scale. To make this work with the existing Nvidia comms library, they also add a scheme to sync up scales across distributed tensors before the all-reduce.

Optimiser

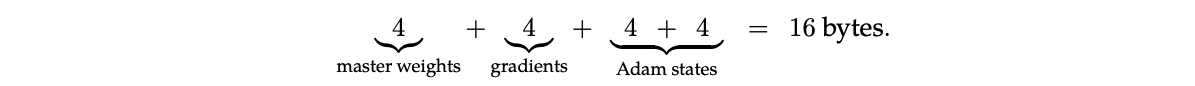

The most basic Adam implementation uses FP32 for all elements (4 bytes):

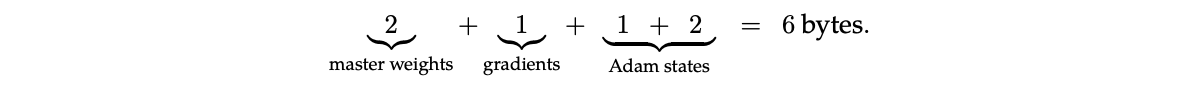

They suggest that the following mix of FP16/8 is viable without degradation:

I think the previous assumption was that the best you could do was (2 + 1 + 2 + 4) here - so intriguing to know that the Adam moment states may be able to go smaller. This is their storage format; it’s not clear what formats are used in the update computation.

Results

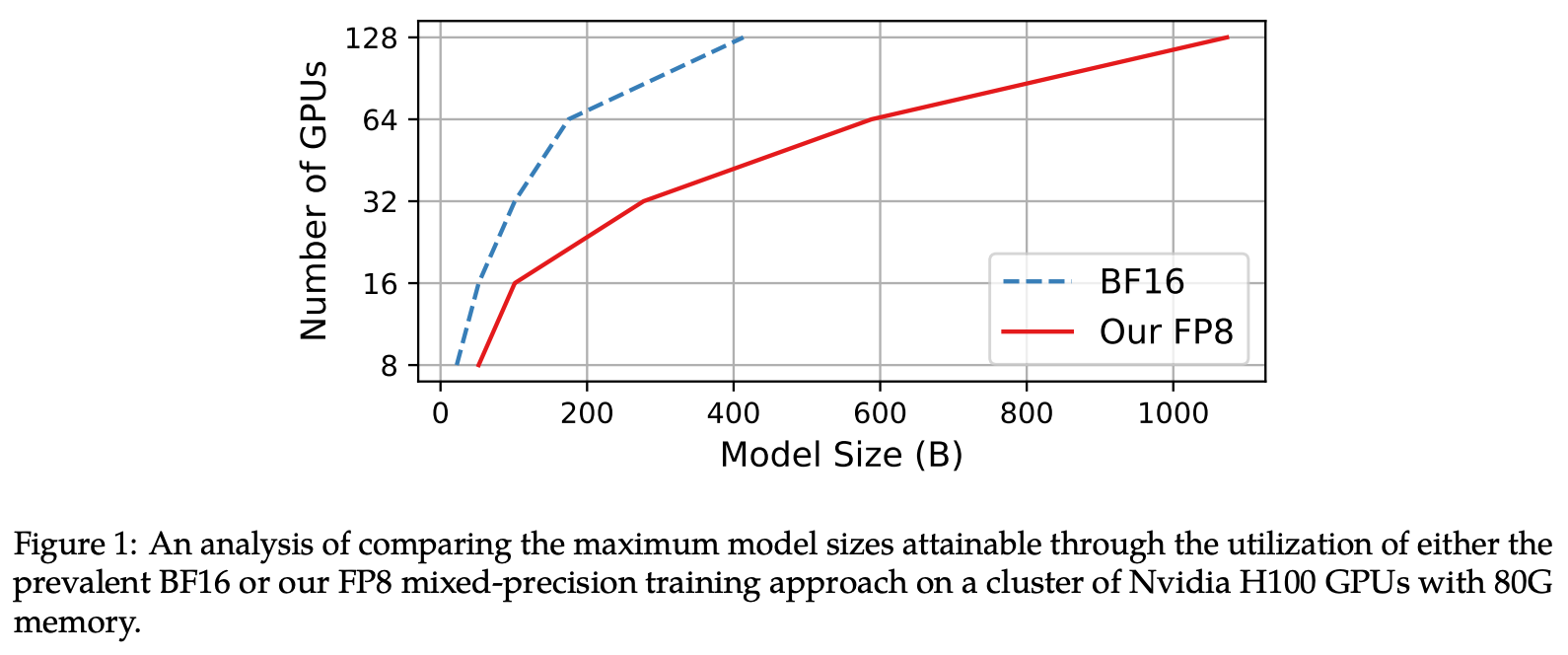

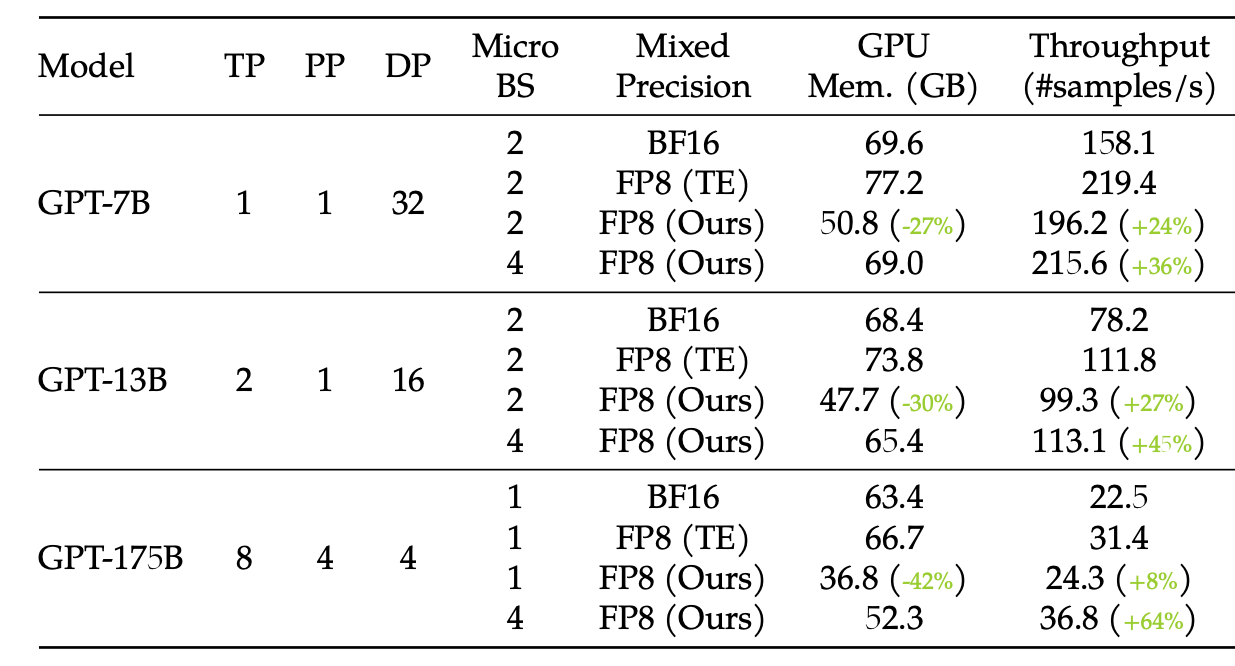

Their method gets significant speedups versus the BF16 baseline, and uses a little less memory (I would have expected a larger improvement? Though they suggest you get more savings as you scale, as in Fig. 1).

In terms of throughput they only beat TE at the large-scale (due to comms being more of an issue here), but there is a consistent memory improvement.

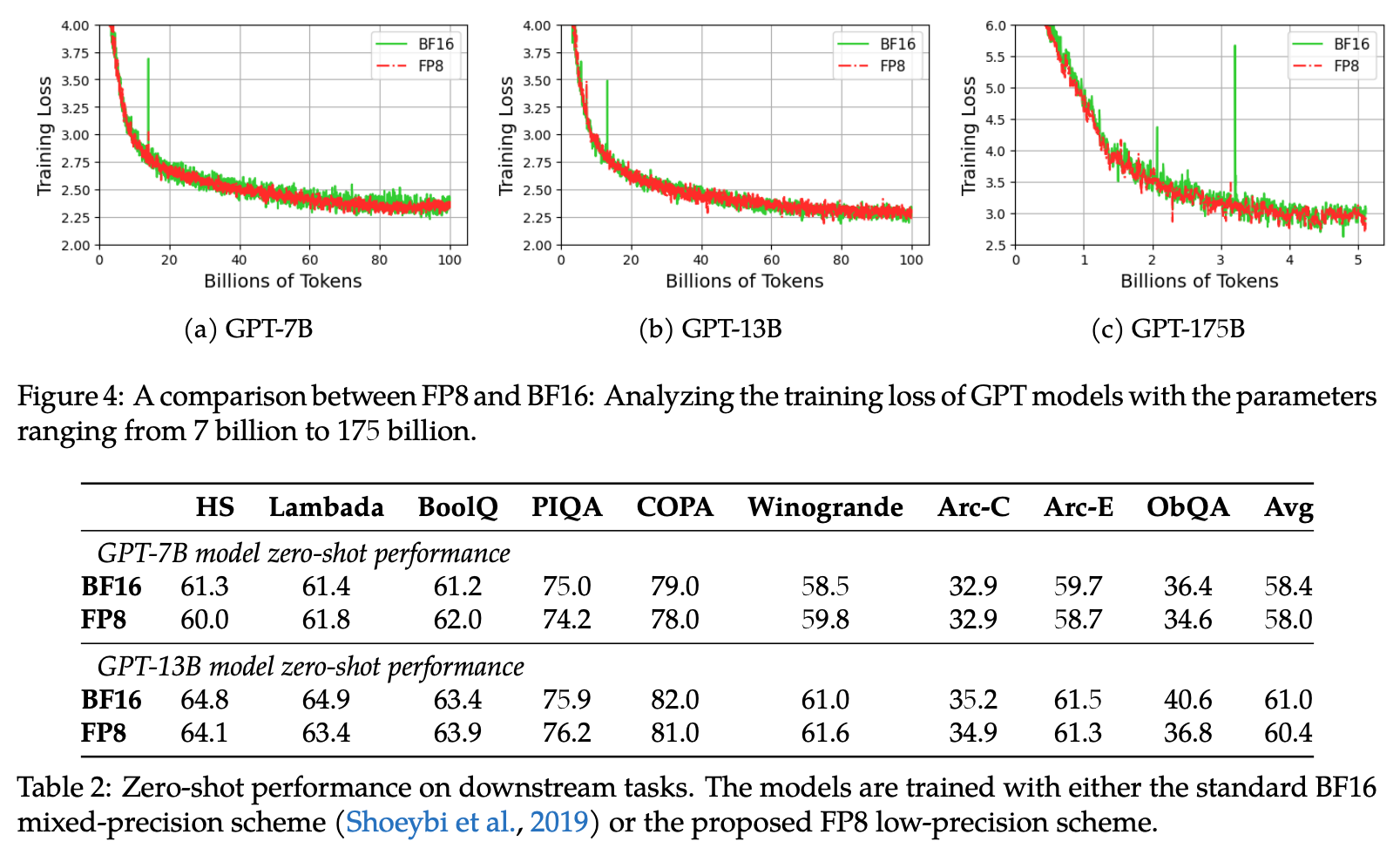

Key to all of this of course is their assertion that these efficiency savings don’t degrade the model. Looking at the loss curves and downstream performance, this seems to hold up:

Overall, their claim to be the best FP8 solution seems justified. I imagine many organisations with FP8 hardware will adopt a trick or two from this paper - especially as they provide a PyTorch implementation.

Comments