Scaling LLM Test-Time Compute Optimally can be More Effective than Scaling Model Parameters

The key idea

When choosing between deployment of a small or large model, consider whether the compute saving made from choosing a small model can be reallocated to improving model outputs at runtime and still retain a net compute gain.

Their method

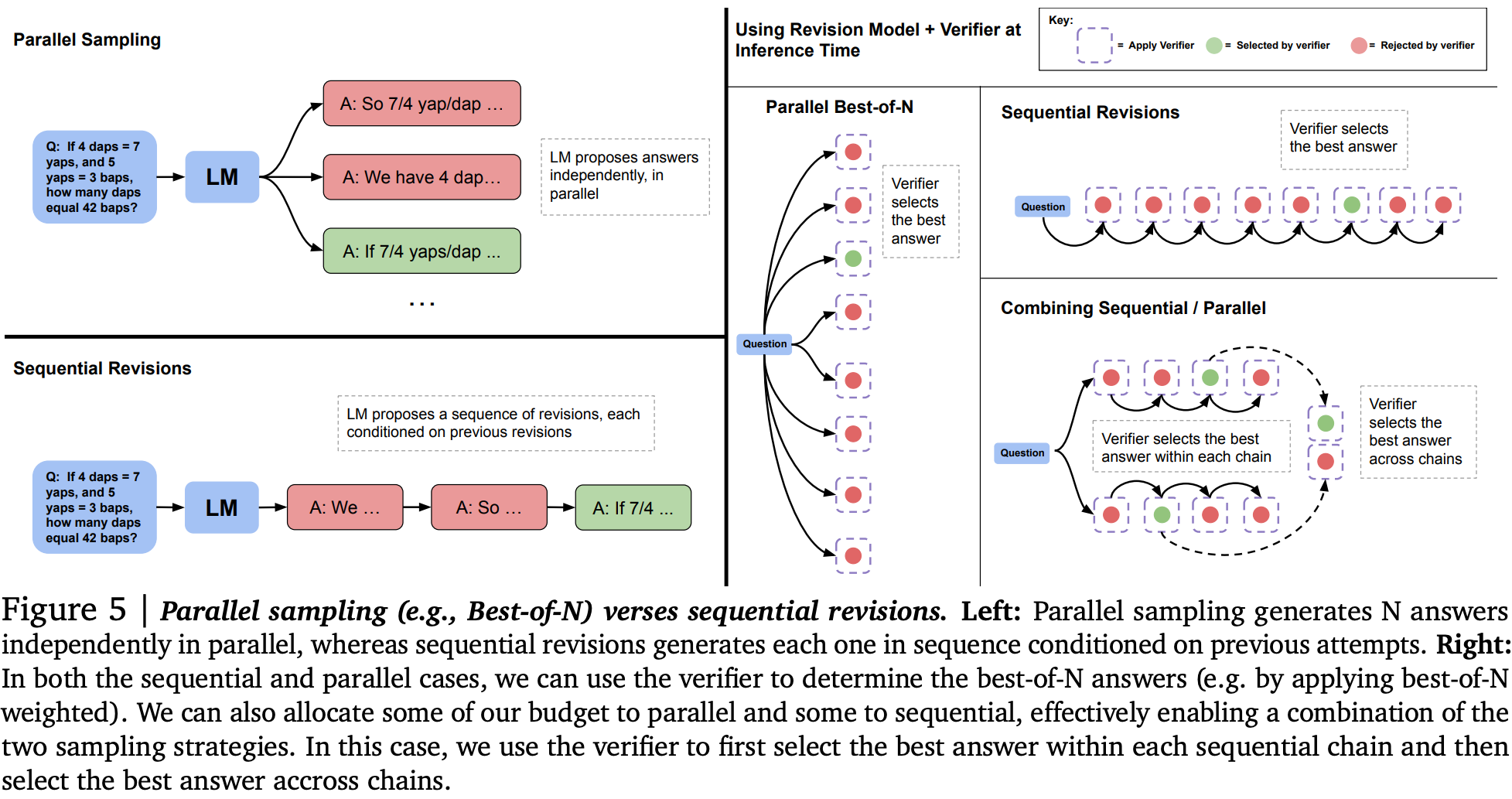

The authors consider how to reallocate compute along two axes:

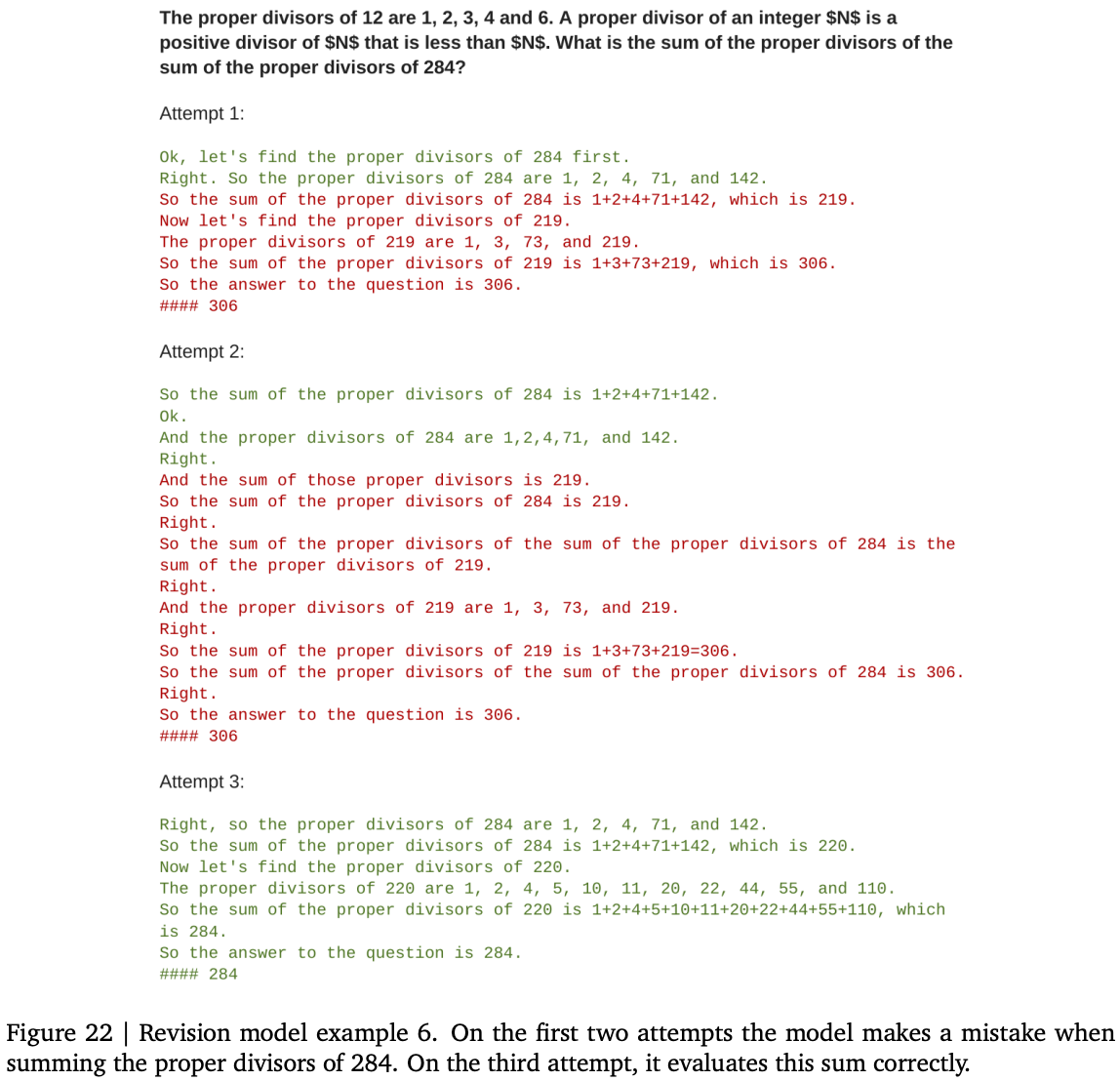

1) Modifying the proposal distribution by augmenting context with additional tokens. To tie this to model compute (rather than independent sources of additional tokens like retrieval), they study self-critique, in which models augment their context with a sequence of incorrect answers to guide themselves towards the correct answer. This requires a bit of fine-tuning, using sequences of incorrect answers followed by correct answers as training data. At inference time, models may generate a correct answer in the middle of the sequence, so they pool all outputs for generating a final answer (e.g., take majority).

Example:

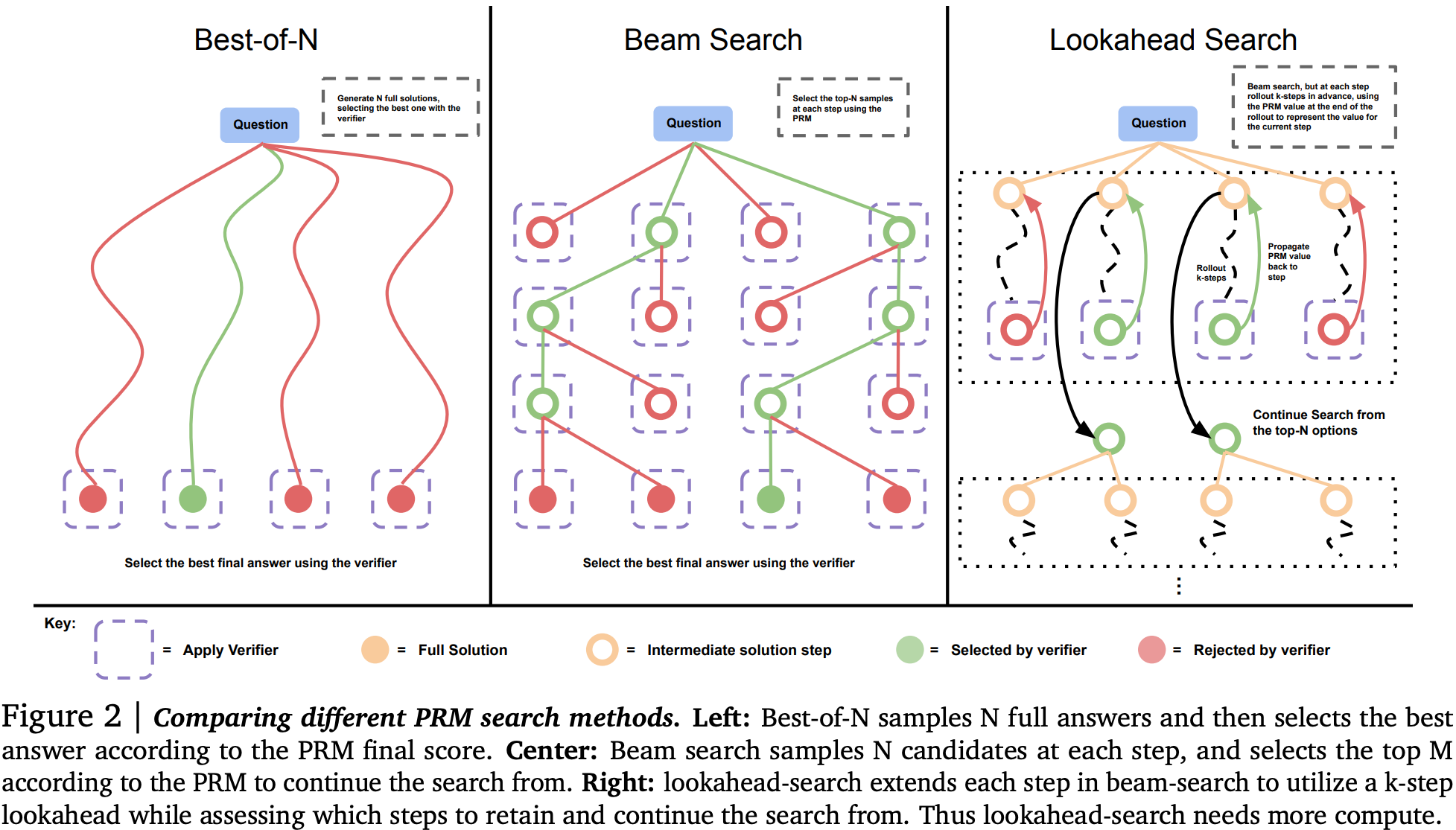

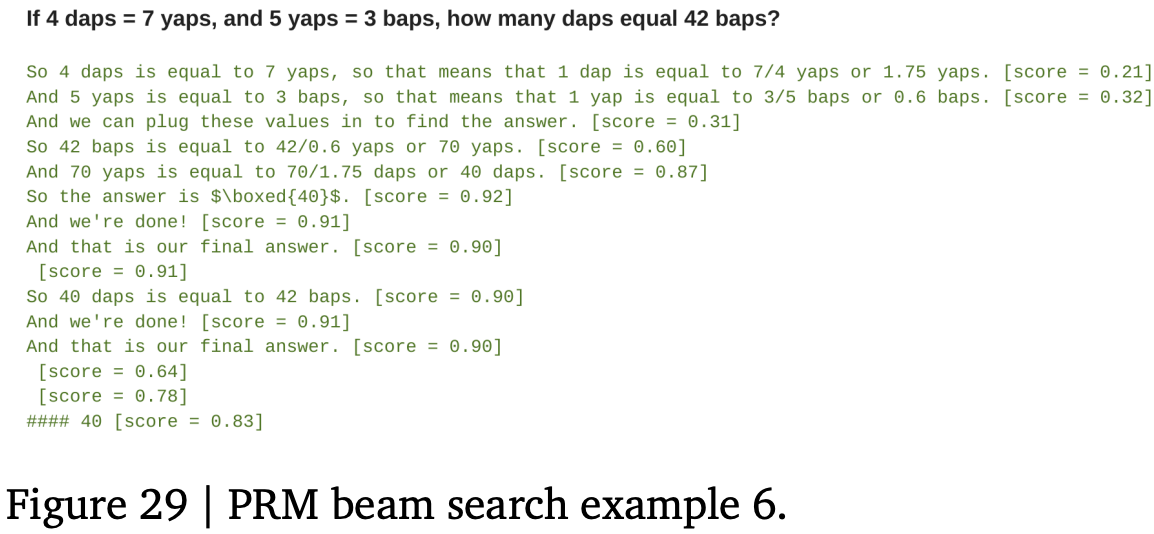

2) Improving the model output verifier with a reward model used to score each generation step in beam search decoding. They use beam search with lookahead as a means to parameterise a fixed compute budget, since number of beams (independent parallel searches), beam width (parallel search with a shared history), and lookahead steps (rollout of search path to evaluate beam at current step) can all be used to scale compute at inference time with many parallel and sequential executions of the model.

Example:

They evaluate each of these approaches independently on high school maths problems (MATH benchmark) binned into 5 separate difficulty brackets based on accuracy rate of a base LLM (PaLM-2).

Results

For each approach, they first define the “compute-optimal” strategy. This amounts to finding the right setting of sequential and parallel compute given estimated question difficulty (as measured by a learned reward model).

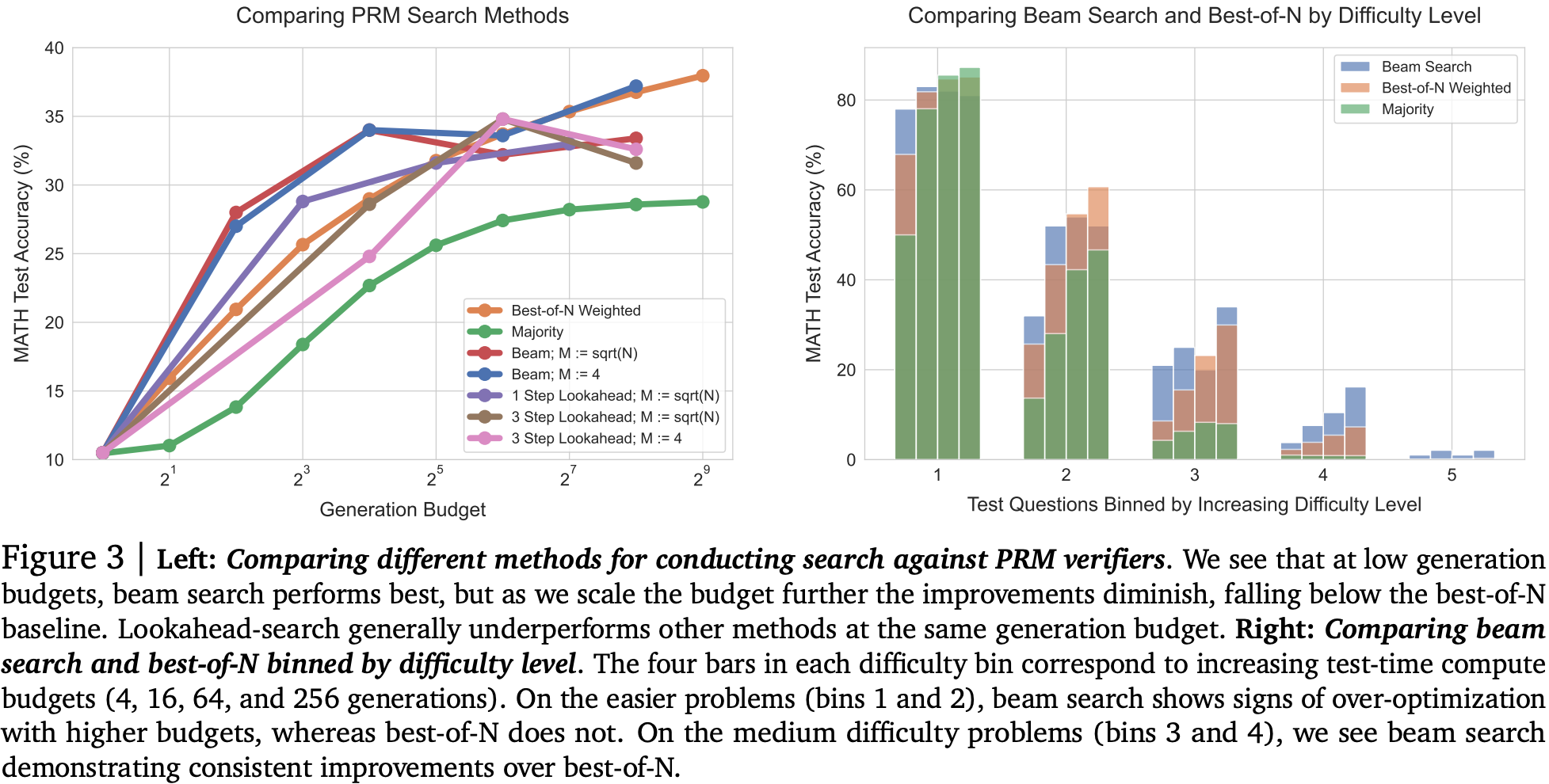

For improving verifiers with a learned reward model + beam search, they find that increasing the number of lookahead steps is worse than simply allocating more/wider beams, i.e, the overhead of lookahead didn’t provide enough of a gain compared to expanding beam search. They also find for easier questions that there appears to be some evidence of reward-hacking, since increasing compute budget made accuracy slightly worse on the easiest questions than with lightweight strategies for verifying outputs. However, for medium difficulty questions, increasing compute budget improved accuracy, albeit from a low bar. On the most difficult questions where simple strategies completely failed, there looks to be a very marginal gain.

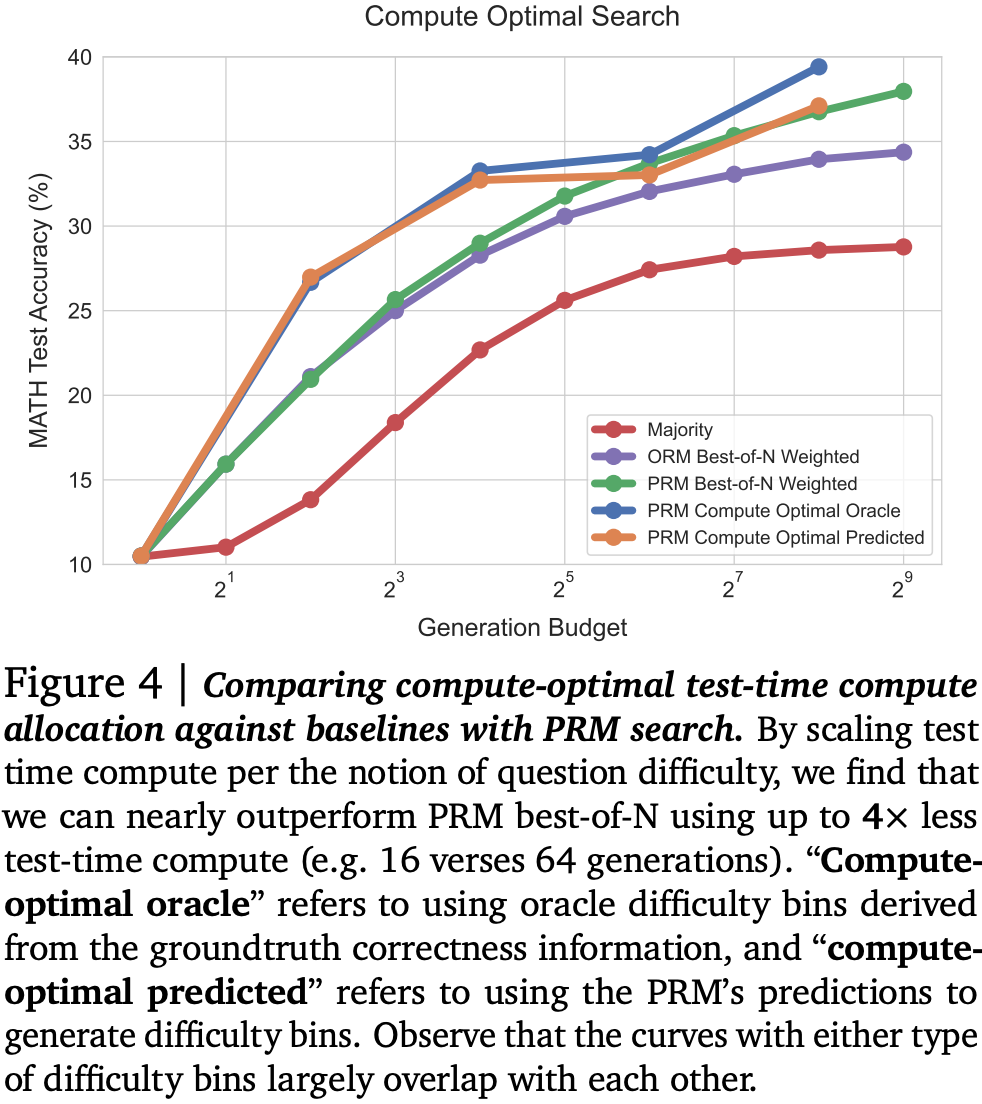

Balancing across these findings to produce a compute-optimal strategy picking the best settings for each compute budget, they show a 4x improvement at lower compute budgets, although this appears to saturate. Interestingly, using estimated rather than “actual” difficulty to pick strategy doesn’t appear to harm accuracy much at all.

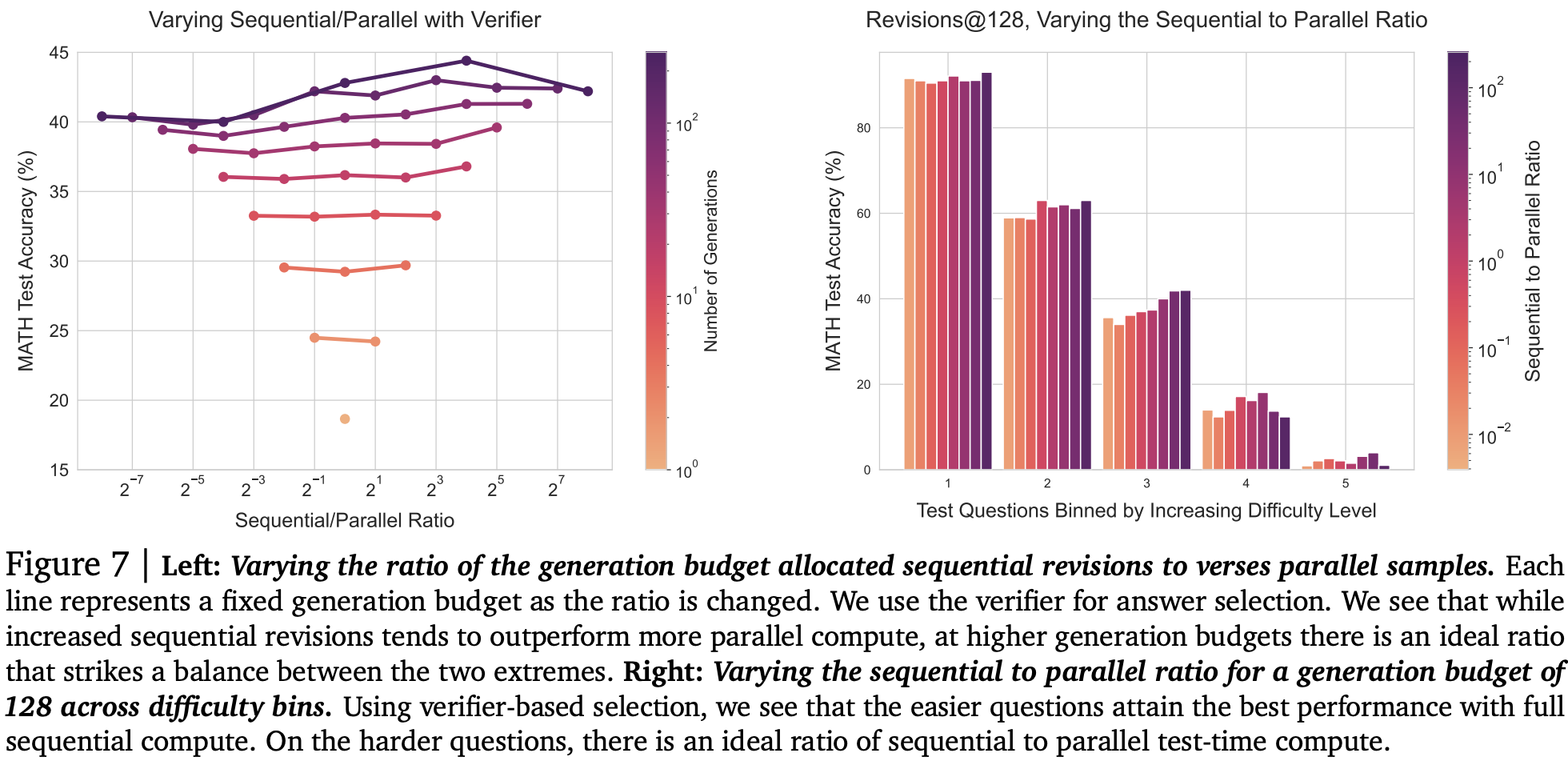

For improving the proposal distribution with sequential revisions they need to find the right balance between spinning up independent sequences of revisions in parallel, and increasing the length of the revision chain. They show that as compute budget increases, more compute should be allocated to generating sequential revisions. Indeed it looks like there might be an easily saturated benefit from generating multiple revision chains (expanding search space), but that the greatest improvement comes from following a chain further down the path (refining search path). Additionally, easy questions seem to benefit more from revisions, but harder questions benefit from a bit more coverage of search space.

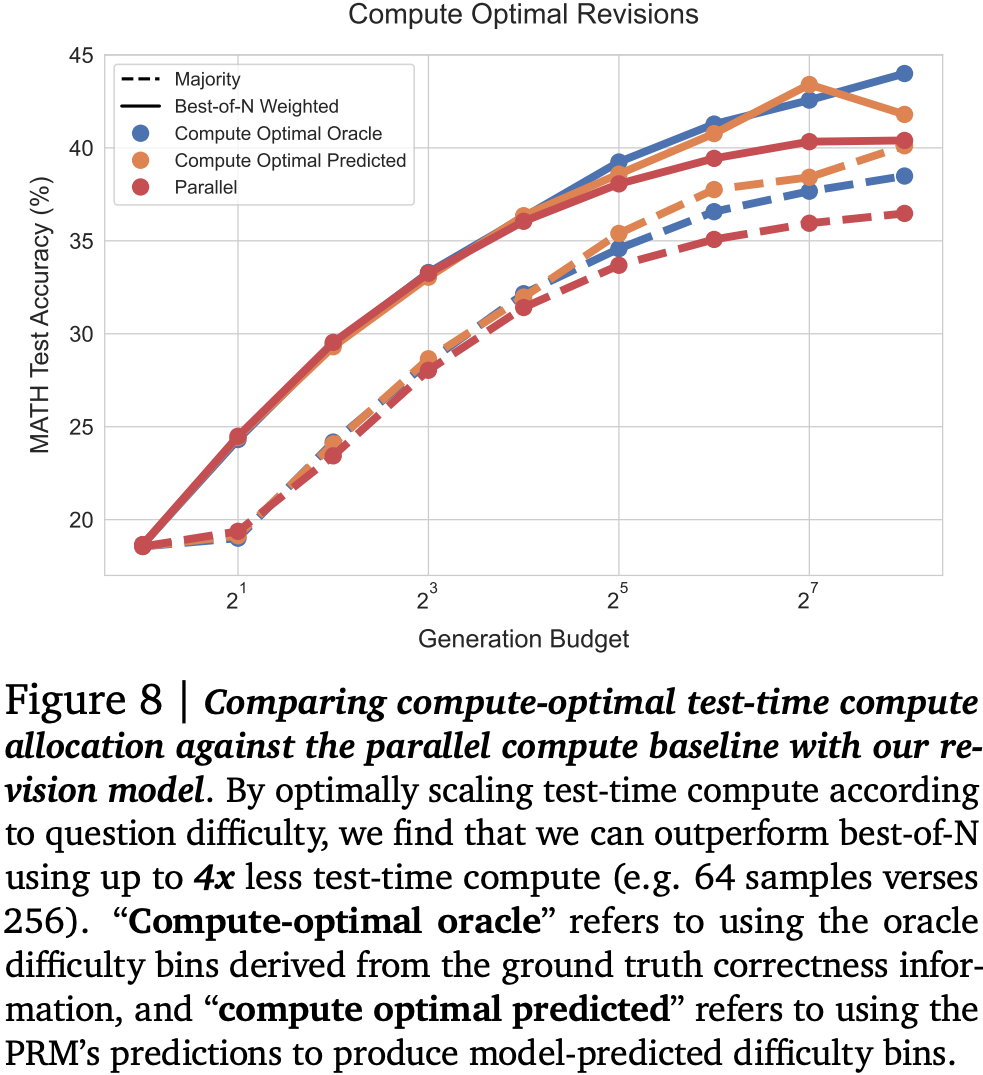

Once again they propose a compute-optimal strategy choosing the best settings for each budget and question difficulty. This time it appears that accuracy continues improving as budget increases.

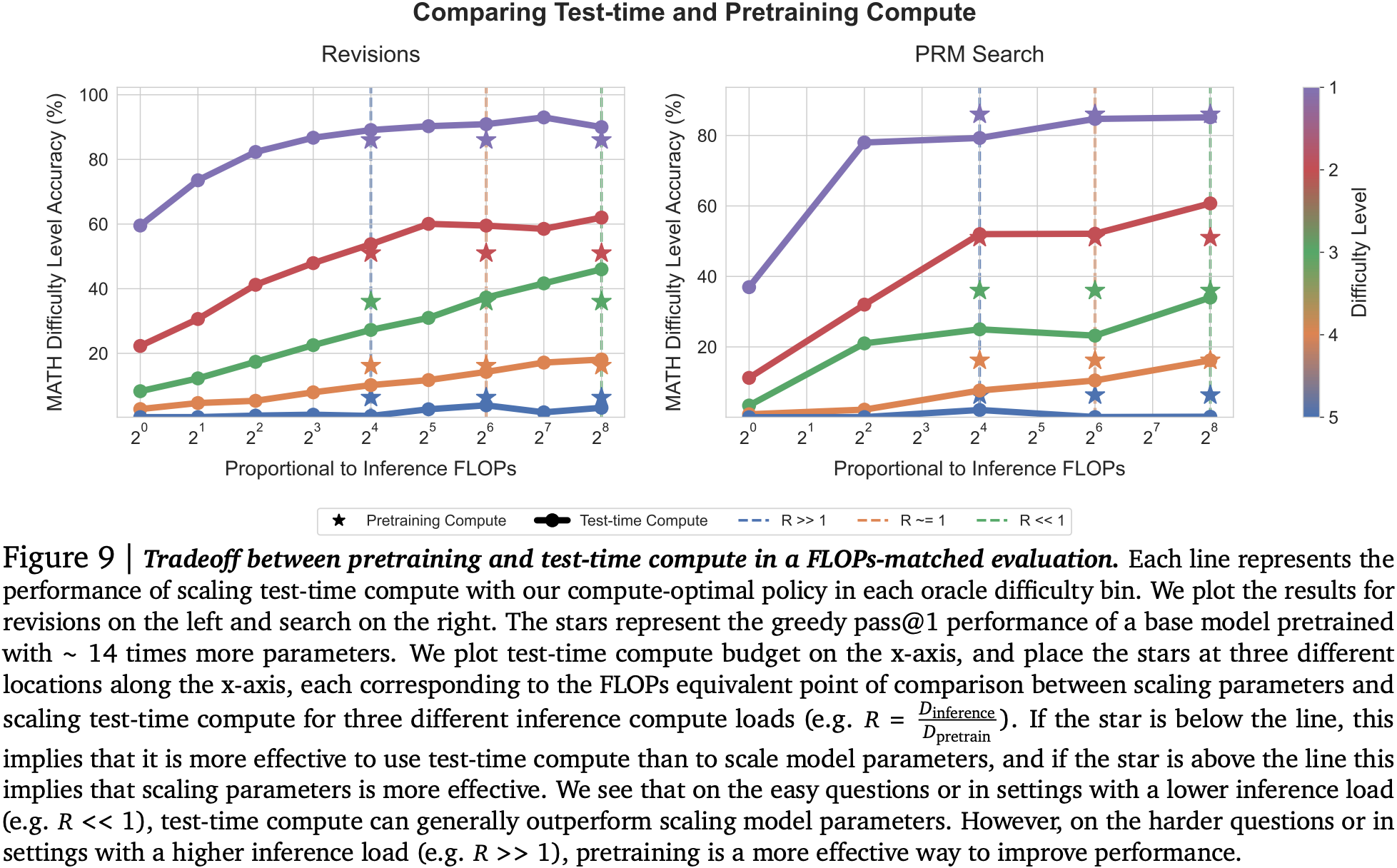

Finally, they examine the trade-off compared with using a larger pretrained model under three different assumptions for how long it would be deployed, i.e., whether the total number of inference token is much less than, similar to, or much greater than the total number of pretraining tokens. Firstly, there doesn’t seem to be much benefit to just improving the verifier: using a larger pretrained model appears to win almost every time. However, allowing the model to revise answers does appear to help, at least in some cases. In particular, you can save compute at test time using a smaller model with sequential revisions for easier questions, especially when number of inference tokens is much less than the total number of pretraining tokens. As you tip the ratio in favour of more inference tokens, the difficulty bar appears to raise meaning fewer medium difficult questions obtain a compute saving from smaller model with revisions. For the most difficult questions, a larger pretrained model always works best. It appears there are diminishing returns for improving a model distribution without a more expressive model in the first place.

Takeaways

A question we have been asking for a while in the research team is how to strike the right balance between in-context learning and finetuning. This paper takes that a step further and also asks whether you should simply improve your pretraining recipe. Of course, in the real world you need to do both since you’ll deploy your current model to the best of its ability before the next one is available. Even in this vastly simplified setting (no consideration of interaction with the myriad other ways to modify models during deployment: RAG, tool-use, quantisation, distillation), you can see some benefit to adding FLOPs at inference time.

Comments