Training Language Models to Self-Correct via Reinforcement Learning

The key idea

Users of LLMs will be aware that sometimes they can recognise and correct their own mistakes. This prompts the question: if the model has the capability to identify some of its own failures, can we leverage this to improve the model?

This is easier said than done. This paper shows that supervised fine-tuning (SFT) — the dominant post-training approach for LLMs — has some inevitable failure modes when trying to teach a model to self-correct. What’s needed, and what they demonstrate, is that an RL-based approach can prevail.

This is significant: true RL has only just broken into the LLM training space, in the form of OpenAI’s o1 model, but few details have been released. This work presents a significant step towards realising the benefits of RL in helping language models to reason better.

Background

The most straightforward approach to solving the self-correction problem is simply:

- Take a dataset of question-answer pairs for some reasoning task

- For each, prompt the model to generate a solution

- Evaluate each and remove those solutions which are correct

- Then prompt the model to generate a correction to the incorrect solution

- Evaluate the final solutions, and now filter out the incorrect ones

- Take this dataset of 2-stage “corrected” answers and train the model on it

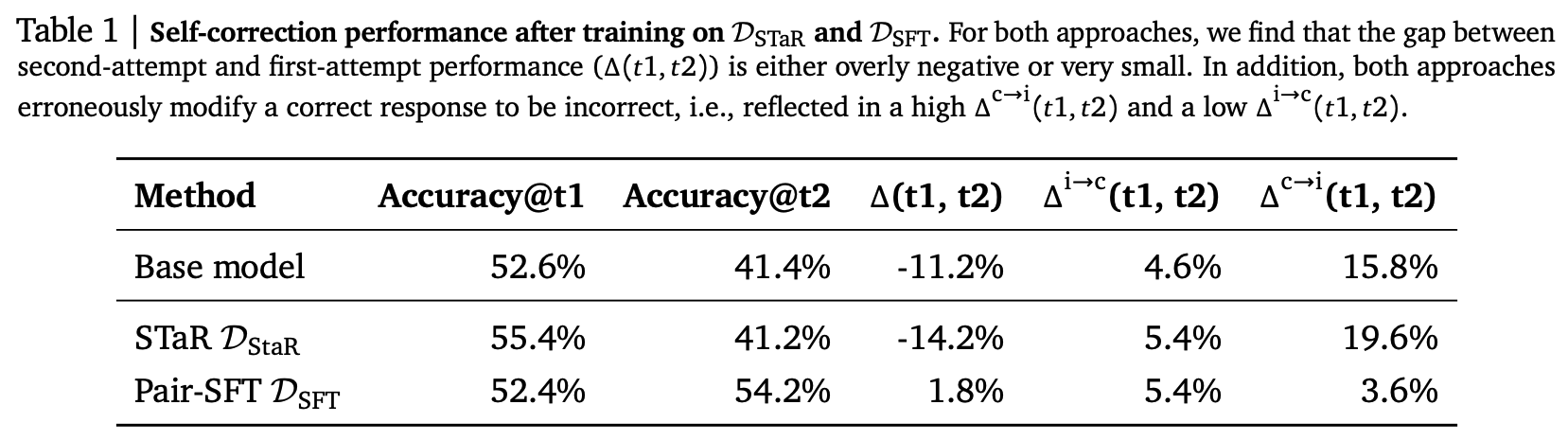

This is the basis of the STaR method, which the authors use as a baseline, alongside PairSFT, which works similarly but uses arbitrary pairs of incorrect-correct responses to a given prompt as training data.

The authors test these methods and see the following:

STaR slightly improves the initial attempt, but is poor at correcting — so much so that it tends to make answers worse, not better! Pair-SFT offers a modest accuracy improvement, though this is largely down to a drop in the value of the final column, which indicates the fraction of correct responses the model ruins via wrong “corrections”. So in summary: the only improvement we really see is the model learning to be much more cautious in correcting itself.

They trace these difficulties down to two problems:

- The model tends towards a minimal edit policy, where it tries to change as little as possible to avoid degrading the original response.

- The model is trained on data from its original distribution over responses, yet training causes this distribution to change, leading to distribution mismatch.

Their method

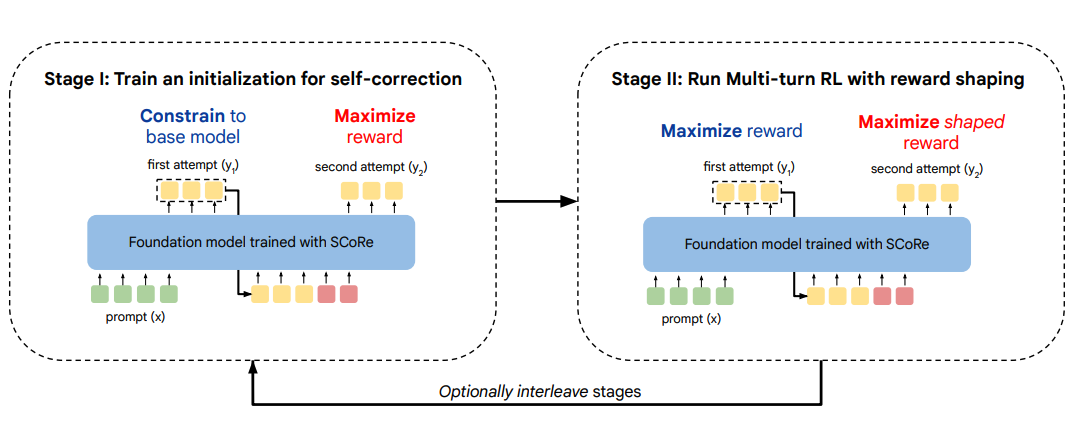

The two-stage RL-based method they design aims to target the problems outlined in turn.

Stage 1: The first stage uses RL to maximise the following objective:

Here $\hat{r} (\mathbf{y_2}, \mathbf{y^*})$ is some “correctness” function that acts as a reward, which crucially is based on $\mathbf{y_2}$, the model’s second attempt at the problem. The KL term acts on the first attempt, encouraging the model to keep its first guess the same as the original (“reference”) model.

We can see from this that the aim is to encourage the model to learn strong correction behaviour, by fixing the first attempt and optimizing just the second (approximately). This addresses the minimal edit problem.

Stage 2: Having encouraged strong correction in stage 1, the full problem is addressed in stage 2, which maximises:

Here the RL objective is over both attempts, with a weaker KL penalty over both acting as a mild regulariser. A reward-shaping step is also used here to up-weight examples where incorrect first attempts are successfully corrected.

The key difference between this and SFT is that the data used to update the model is always generated by the current model. This avoids the distribution mismatch problem.

Results

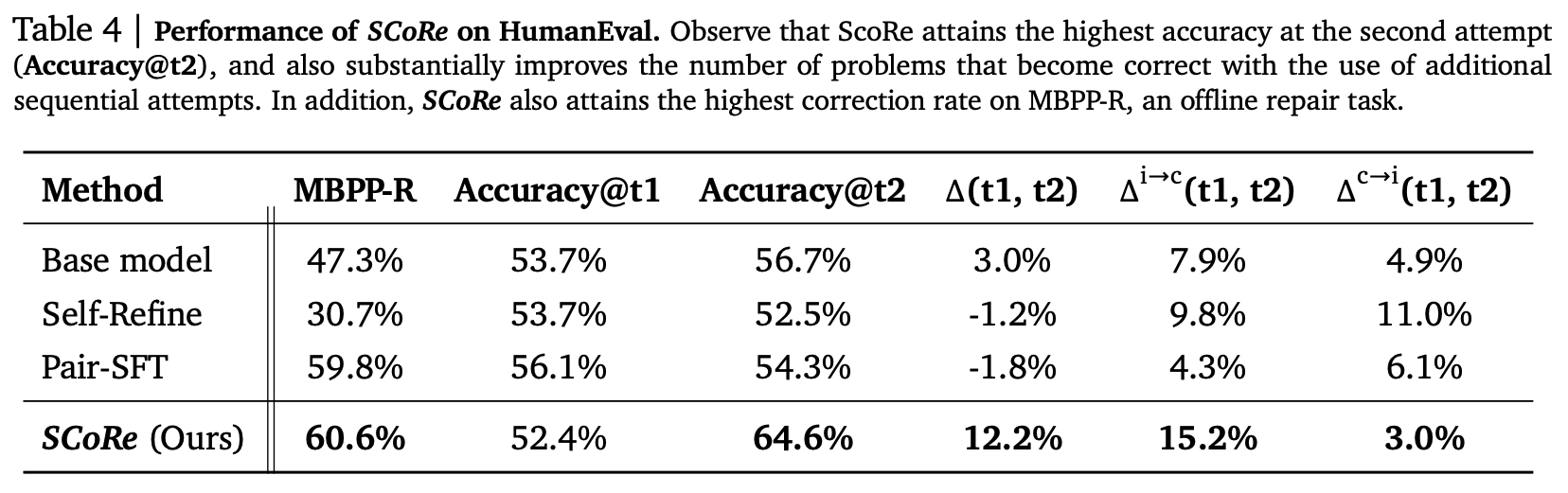

In short, it works. Results are good on maths problems, and even better on coding tasks:

The first-attempt accuracy is slightly degraded, but the second attempt is substantially better than any other attempt by other methods. The main reason for this is shown in the second-to-last column: a large increase in incorrect answers becoming correct, which is the key objective.

The paper shows several other evaluations and ablations, making a strong case for the method.

Takeaways

This paper makes a compelling case for why supervised fine-tuning is limited as a post-training procedure, and for some problems (such as self-correction), some kind of on-policy RL is required. Carefully designed objectives are required to make this work, but it appears to significantly boost a model’s ability to reason at inference time.

This is just the start. The authors consider a fairly simple problem setting: a single correction attempt on a zero-shot answer, with no supervision as to the source of error. One could imagine a similar approach with many correction attempts, possibly on chain-of-thought responses, and with more granular feedback. This promises to be a significant direction of future LLM research, with significant computational and algorithmic implications.

Comments