Massive Activations in Large Language Models

The key idea

All LLMs exhibit very large activation values after a few layers — a major challenge for LLM quantisation. This paper shows why: massive activations are the transformer’s way of attempting to add a fixed bias term in the self-attention operation. The authors also demonstrate a neat solution based on this analysis.

Background

Papers like LLM.int8() and SmoothQuant previously studied a similar problem with large activation values appearing, termed outlier features. The authors claim that massive activations are a slightly different phenomenon though:

Conceptually, a massive activation is a scalar value, determined jointly by the sequence and feature dimensions; in contrast, an outlier feature is a vector, corresponding to activations at all tokens.

It’s not entirely clear whether these two phenomena are linked. Specifically, in this paper they focus on activations after the residual-add operation.

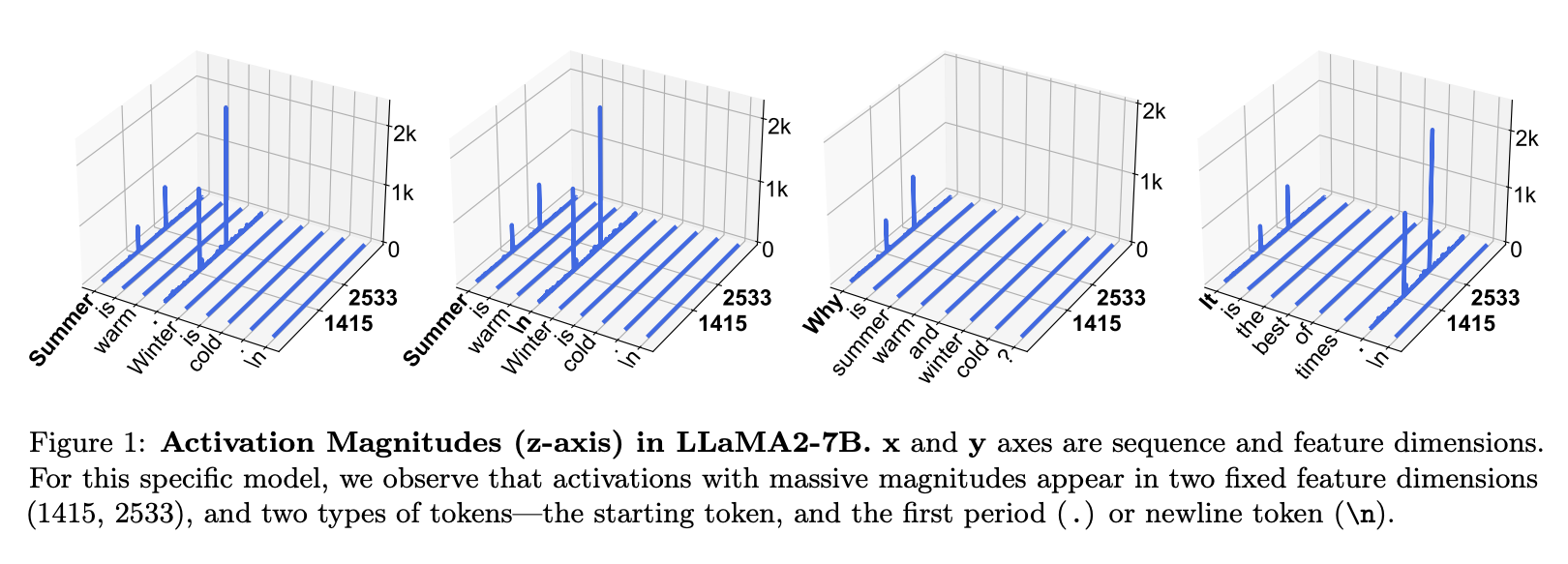

Massive activations are very rare (0.01% for Llama2-7B) and appear in specific dimensions for particular tokens.

Their method

The authors first observe that a set of massive activations often have very similar values to each other. In fact, setting them to a fixed mean value doesn’t degrade performance, but setting them to zero does.

Through a series of steps this leads them to the observation that the massive activations are acting as a fixed attention bias. The mechanism for this is as follows:

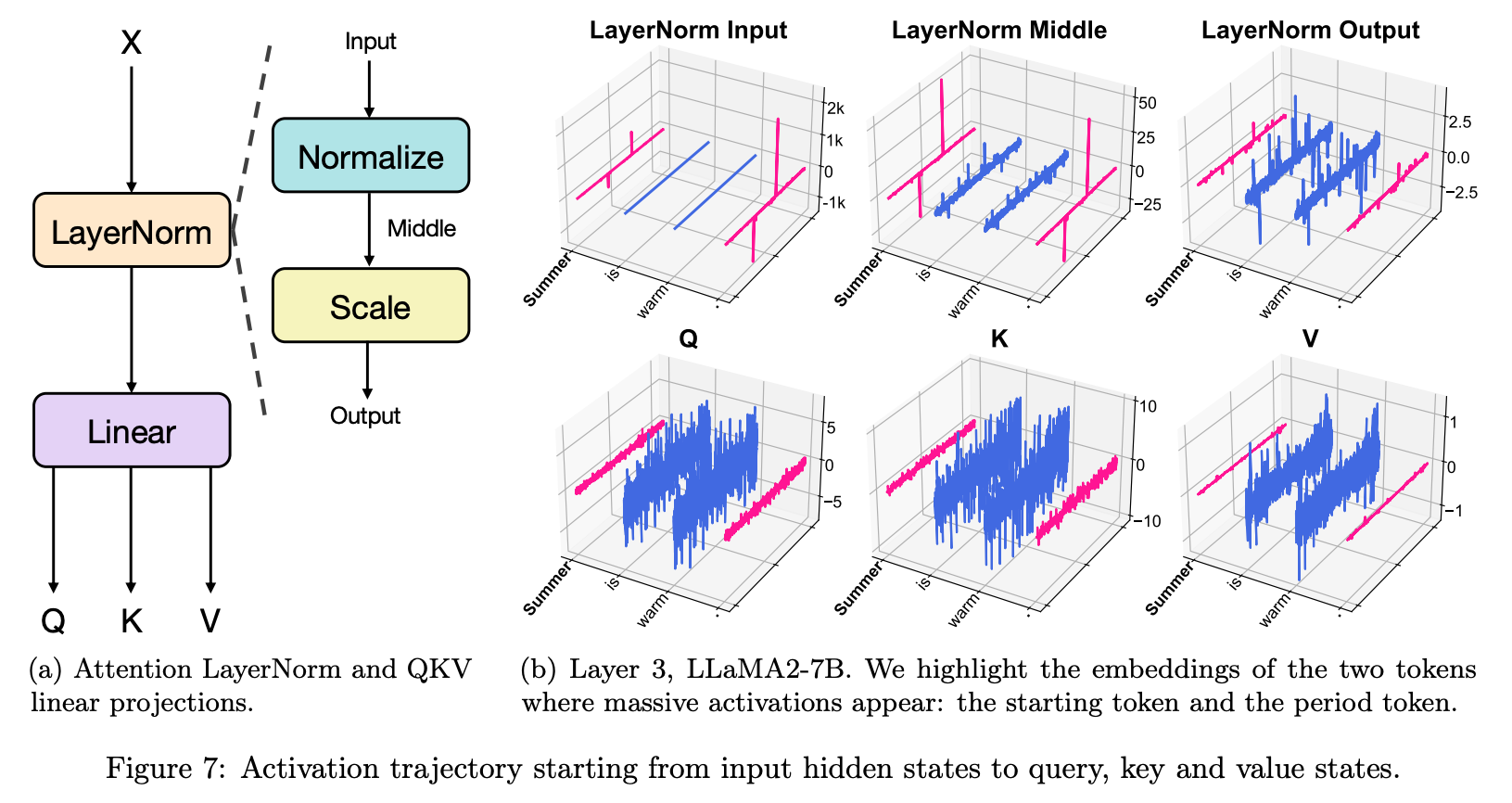

- Massive activations hit the LayerNorm, causing the token-vectors containing them to shrink to the scale of regular token-vectors. Massive-activation tokens now look like one-another: sparse and spiky.

- These representations are then projected into Q, K and V. The massive activations are gone, but those tokens that had them now all have similar representations.

- As the resulting V terms for these tokens now all look the same, this has the effect of adding a constant bias vector to each attention output.

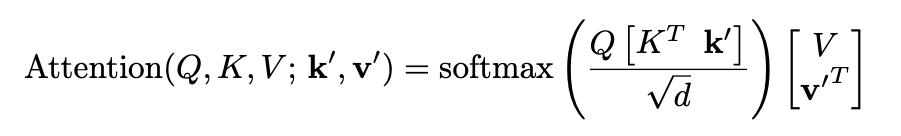

The key observation here is that the transformer has essentially learned a “hack” to add this bias to the attention output, as it’s not present in the original transformer. From this an improved method is derived: add additional trained parameters $\mathbf{k’}, \mathbf{v’} \in \mathcal{R}^d$ as an explicit attention bias for each head:

Results

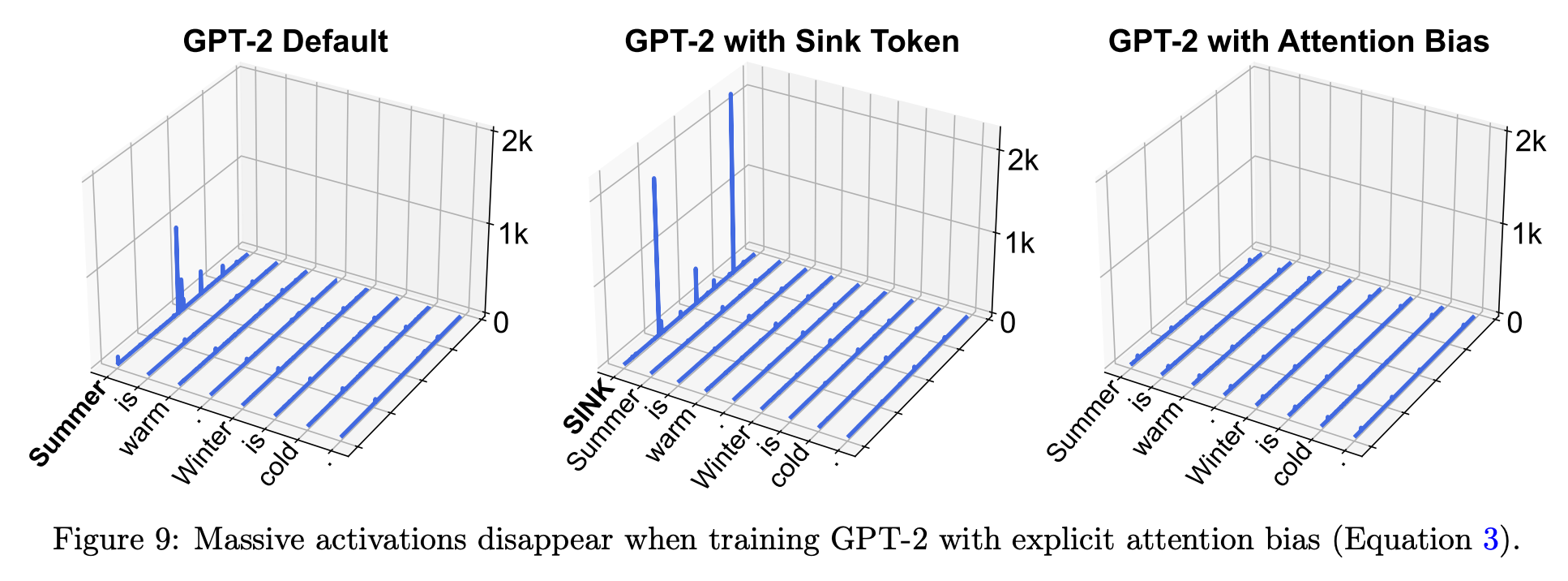

They train three GPT-2 models: a regular one, one with a sink token, and one with their new attention bias. Each reaches the same performance, but the latter no-longer has massive activations.

Similar conclusions are reached for vision transformers, where it’s also shown that the recently proposed register tokens serve a similar role to attention biases.

It’s worth noting here that although activation magnitudes have dropped, some are still over 100. It would be valuable to see work that investigates these medium-scale activations.

Takeaways

This kind of work investigating transformer internals is really valuable. Although massive activations don’t directly harm performance, their presence has significant side-effects.

The most obvious of these is quantisation, where they can force us to use more bits than necessary to represent these outlier values. More generally, our ability to innovate in model design may be limited by the need for architectures that can accommodate learning these attention biases (explicitly or implicitly). Understanding this mechanism gives us the potential to build better and more efficient models.

Comments