Scaling Deep Learning for Materials Discovery

The key idea

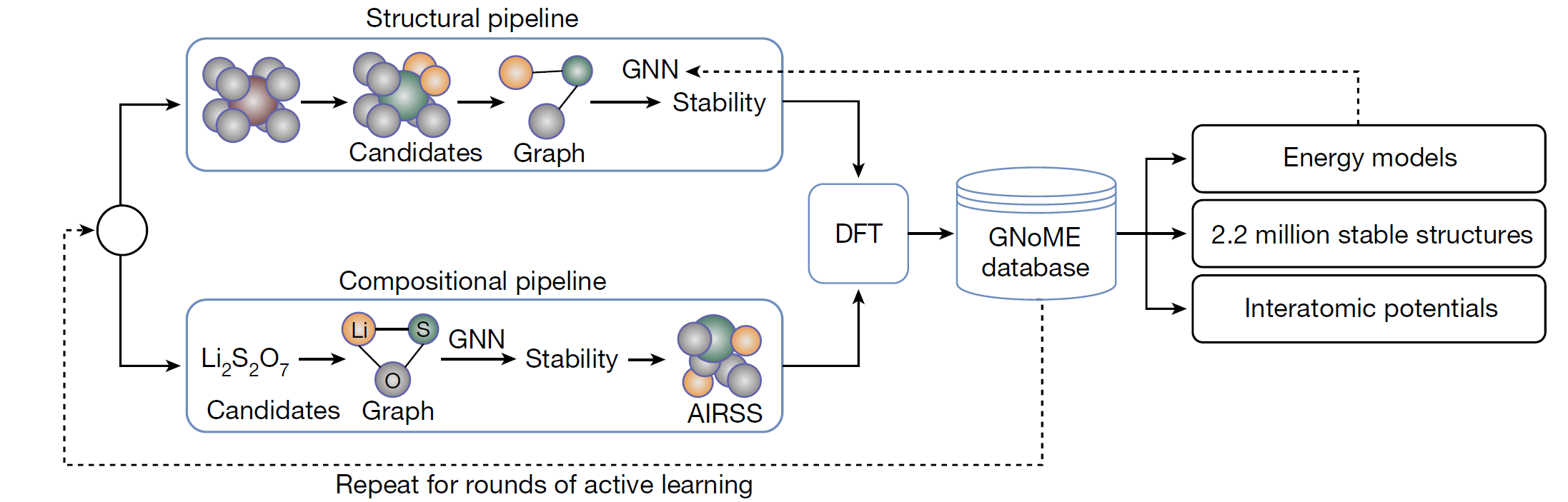

The paper presents a strategy to efficiently explore the space of possible inorganic crystals, employing Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) to filter candidate structures for further expensive computational modelling using Density Functional Theory (DFT). By incorporating the new properties predicted using DFT back into the training set and periodically retraining the GNN, the authors describe an active learning approach that bootstraps their discovery process.

Background

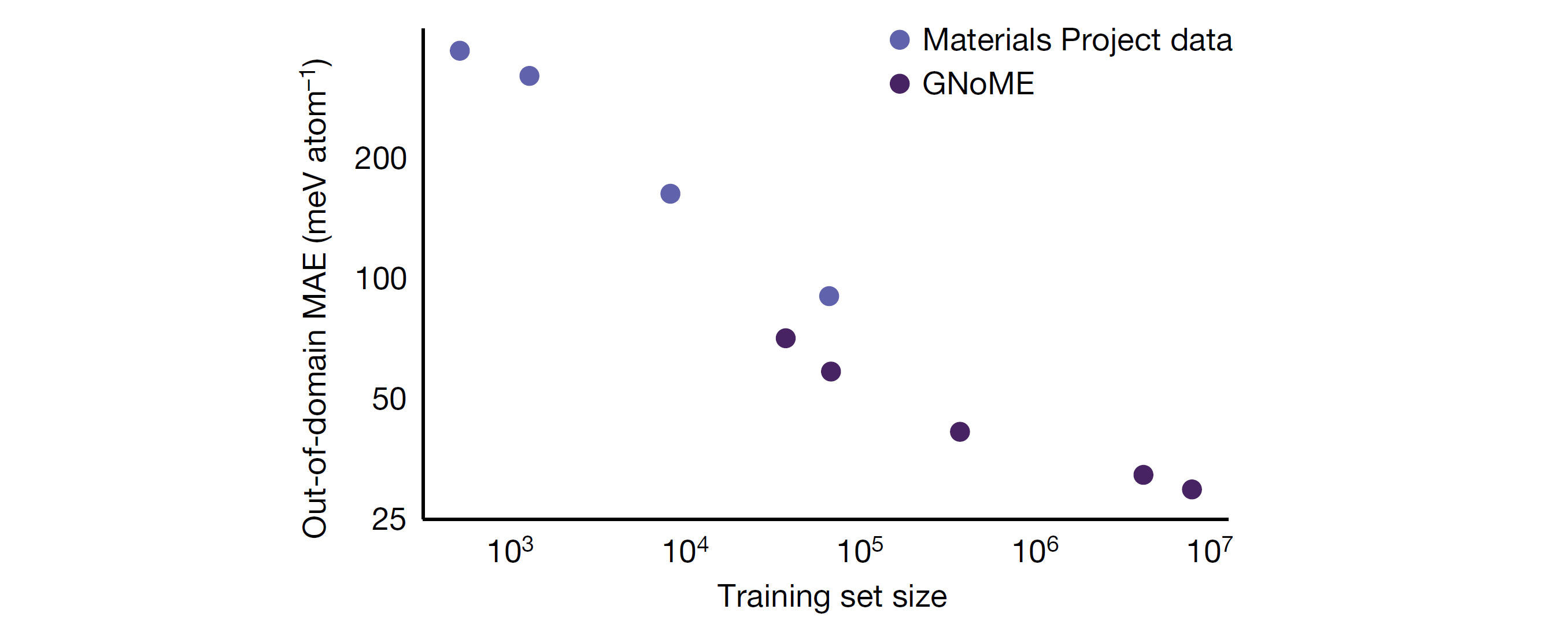

The discovery of energetically favourable inorganic crystals enables breakthroughs in key technologies like microchips and batteries, but traditionally the discovery process is bottlenecked by expensive physical experimentation or first-principal computational simulations. There has been great interest in machine-learning approximations of computational methods such as Density Functional Theory (DFT), but so far they have not been successful in predicting crystal stability. Quantity of available training data is often seen as a limiting factor.

Their method

For breadth of search, the authors employ two frameworks for candidate generation.

The Structural Pipeline: Here new candidates are formed by modifying existing crystals, prioritising discovery and incorporating symmetry-aware partial substitutions to efficiently enable incomplete replacements. Candidates are filtered using the GNoME models, and employ a deep ensemble strategy to quantify uncertainty.

The Compositional Pipeline: Compositional models predict stability without structural information (just using the chemical formula). After filtering using GNoME models, randomised structures are evaluated using Ab Initio Random Structure Search (AIRSS).

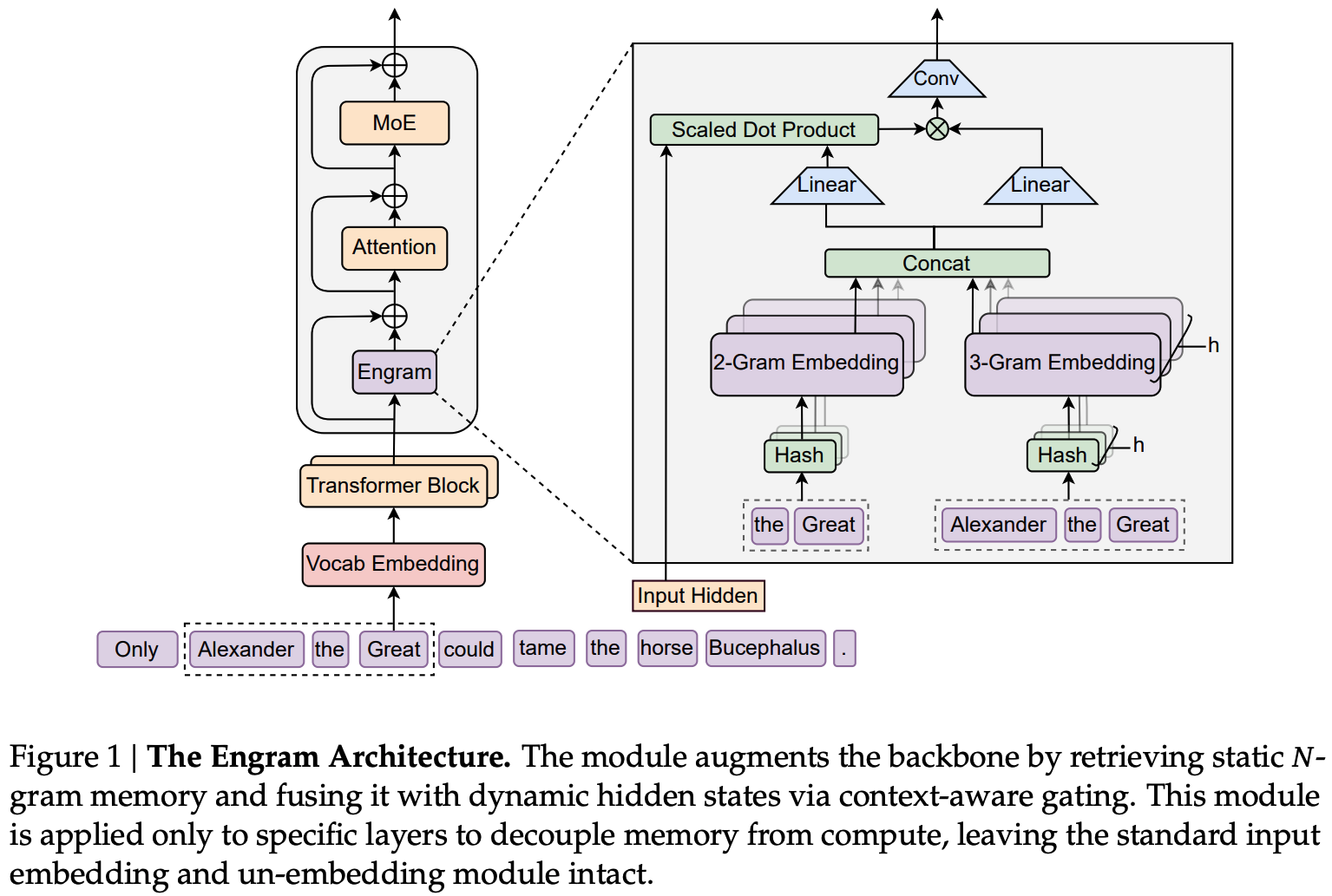

The GNoME models are message-passing networks which take one-hot embedded elements as nodes and predict the total energy of a crystal. In Structural models, there is a node per atom, and edges are added to the graph between any two nodes that are closer than an interatomic cut-off distance. However, for Compositional models, there is one node per element present, and the relative frequency of each element is encoded by scaling the magnitude of the embeddings. An edge is added between every node, so these GNNs begin to look a bit like a Transformer operating on the chemical formula.

Results

Exploration using GNoME has produced 381,000 new stable materials, which the authors suggest is an order of magnitude larger than the set of previously known materials. 736 of these have since been physically realised in a laboratory setting.

Comments