Matryoshka Quantization

The key idea

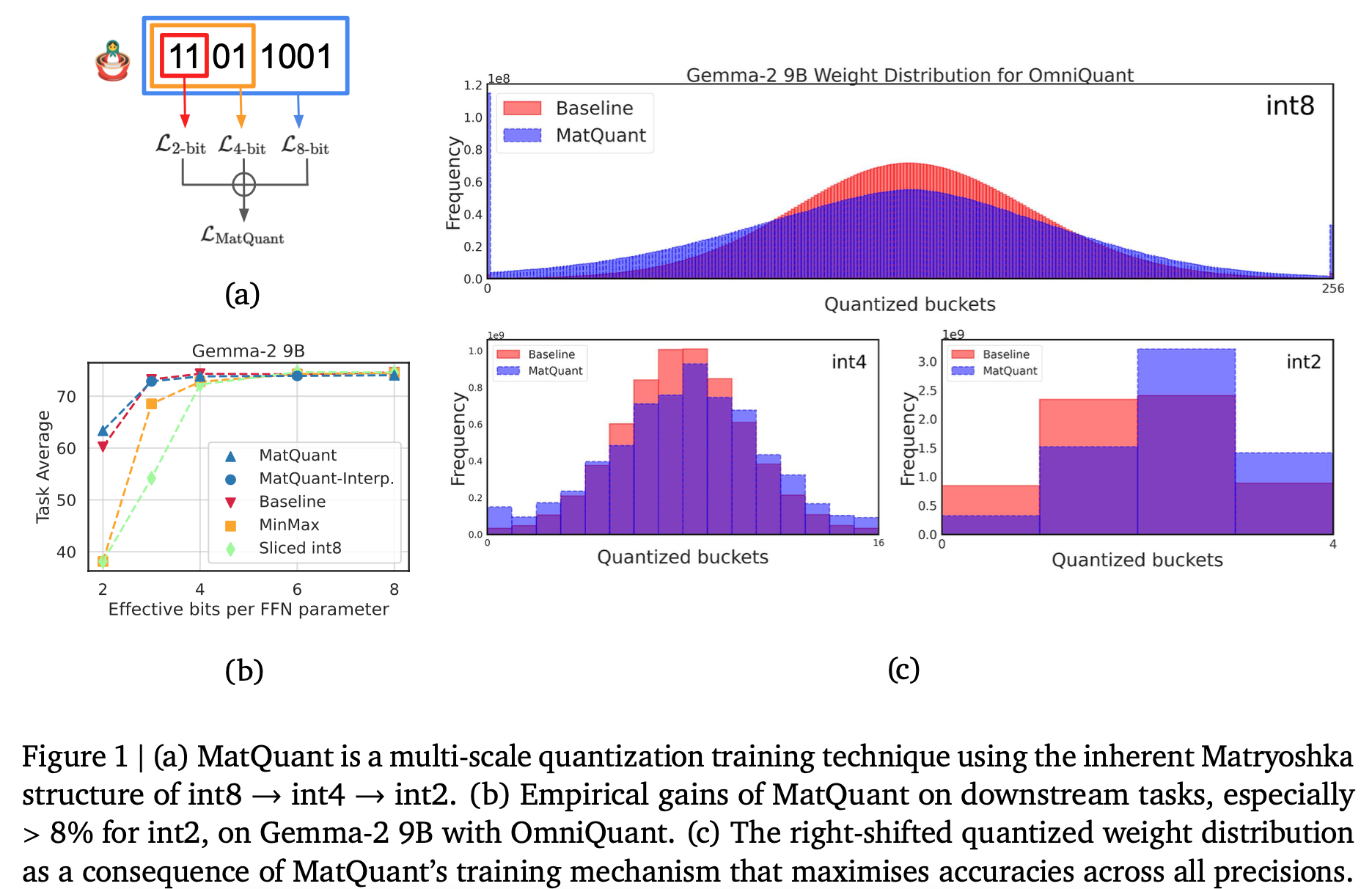

The authors showcase a method for training a single quantised model (from a pre-trained checkpoint) that can be used at different precision levels. They achieve this by simultaneously training the model to work at int8, int4, and int2 precisions, by optimising (at the same time) the eight, four, and two most significant bits of the integer representation, respectively. They show that this approach can be used in conjunction with learning-based quantisation methods, leading to minimal degradation at 8-bit and 4-bit precision levels (compared to optimising for a single precision level), and significantly improving the int2 baseline.

Background

Quantisation methods are broadly classified into two categories: learning-free and learning-based. Learning-free methods independently quantise the model’s layers by minimising each layer’s output error on a small calibration dataset, and generally do not involve backpropagation. Due to this, they are computationally cheaper, but tend to perform worse at very low-bit quantisation. Learning-based methods tend to perform better at low-bit precision, at the cost of the more computationally expensive learning through backpropagation.

The authors focus on two gradient descent-based methods that they show can be used with their Matryoshka Quantisation (MatQuant) approach: quantisation-aware training (QAT) and OmniQuant.

Quantisation-Aware Training (QAT)

QAT learns the quantised weights by minimising the end-to-end cross-entropy loss through gradient descent. The loss can be defined either in terms of the next-token prediction on a training dataset, or minimising the output differences between the original and the quantised models.

As the parameter quantisation function is non-differentiable, training is usually conducted by applying a straight-through estimator for the quantised parameters, i.e., the quantisation function is regarded as an identity function during the backwards pass calculation.

OmniQuant

Like the “learning-free” methods, OmniQuant finds the quantised weights by minimising the output difference (between the original and the quantised model) of each layer independently; however, this is done by introducing additional scaling and shifting parameters that are optimised through backpropagation. As such, it is a computationally cheaper approach compared to QAT, as it only optimises over these additional parameters.

Their method

Quantisation methods discussed previously optimise a model at a single predefined precision. On the other hand, the proposed technique, MatQuant leads to an integer-quantised model, that can be used at different precision levels during inference. This is done by adding individual loss functions for each of the 8/4/2 most-significant bits of the integer representation, which can be used in conjunction with the standard learning-based methods. To obtain an $r$-bit representation from the full $c$-bit one, the numbers are first right-shifted by $c-r$ bits, followed by a left-shift of the same order (with appropriate rounding). The individual-bit losses can then be summed up with additional scaling factors controlling the relative magnitude of each term in the loss.

This scheme changes the obtained quantised weight distribution compared to the baseline techniques: in Figure 1c, the weights tend to have larger magnitudes.

Results

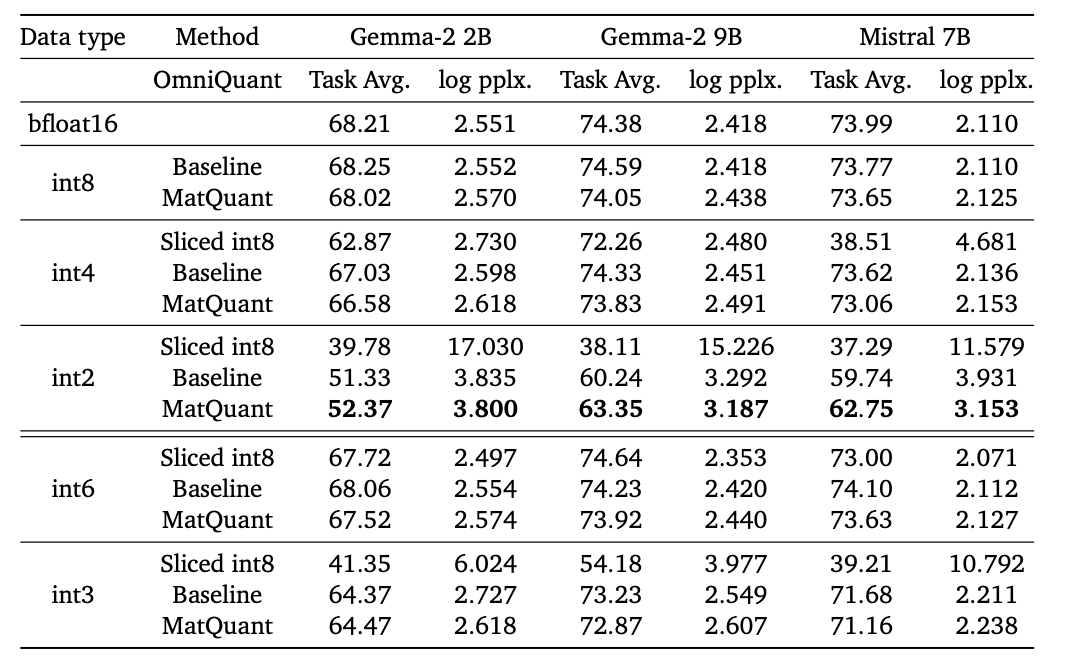

The authors test their method using both OmniQuant and QAT approaches, optimising for 8, 4, and 2-bit integer precisions; the baseline numbers are the two methods used on a single precision level. The methods were tested using Gemma and Mistral models, on a variety of downstream tasks.

Main observations:

- On both QAT and OmniQuant, their method experiences some degradation at

int8andint4precisions, but improves the baseline onint2. - Although training was explicitly conducted using 8/4/2-bit precisions,

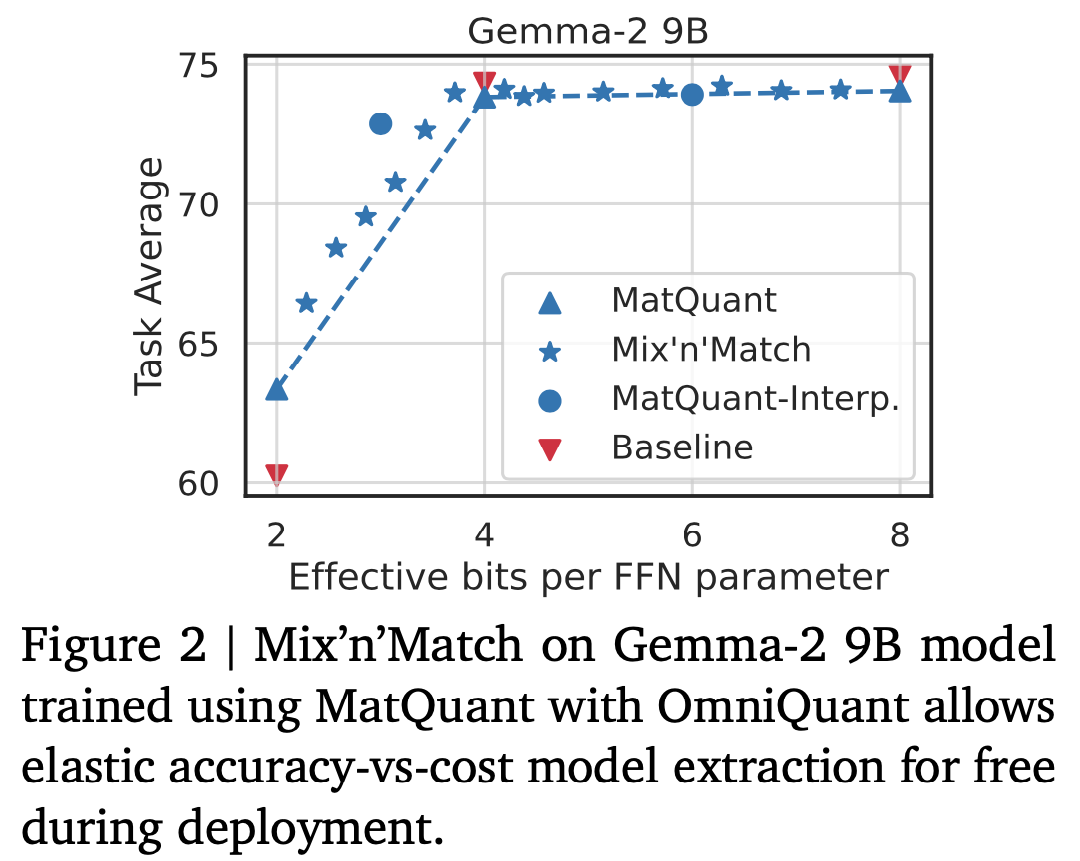

int3andint6show similar performance compared to their baselines (that are trained explicitly at these precisions). - After training, different precision can be applied to different layers: somewhat surprisingly, the authors find that keeping the middle layers in higher precision improves the trade-off. Figure 2 shows the best mix-and-match results for Gemma-2 9B model.

Takeaways

Overall, the authors showcase a neat approach to optimising a flexible-precision integer model using a single training setup – this approach is however limited to integer types, as floating point numbers do not have the “nested” structure that allows for the trivial bit slicing.

Comments