Memory Layers at Scale

The key idea

When scaling up LLMs, we usually increase the number of trainable parameters and the amount of training/inference compute together. This is what happens if you increase transformer width or depth since each parameter is used once per input token. In contrast to this, memory layers add a large but sparsely accessed “memory” parameter, allowing a vast increase in trainable parameters with a minimal increase in training and inference compute. This paper adapts previous ideas for memory layers to produce a model architecture that works at scale and compares favourably to the dense Llama 2 and Llama 3 families.

Background - memory layers

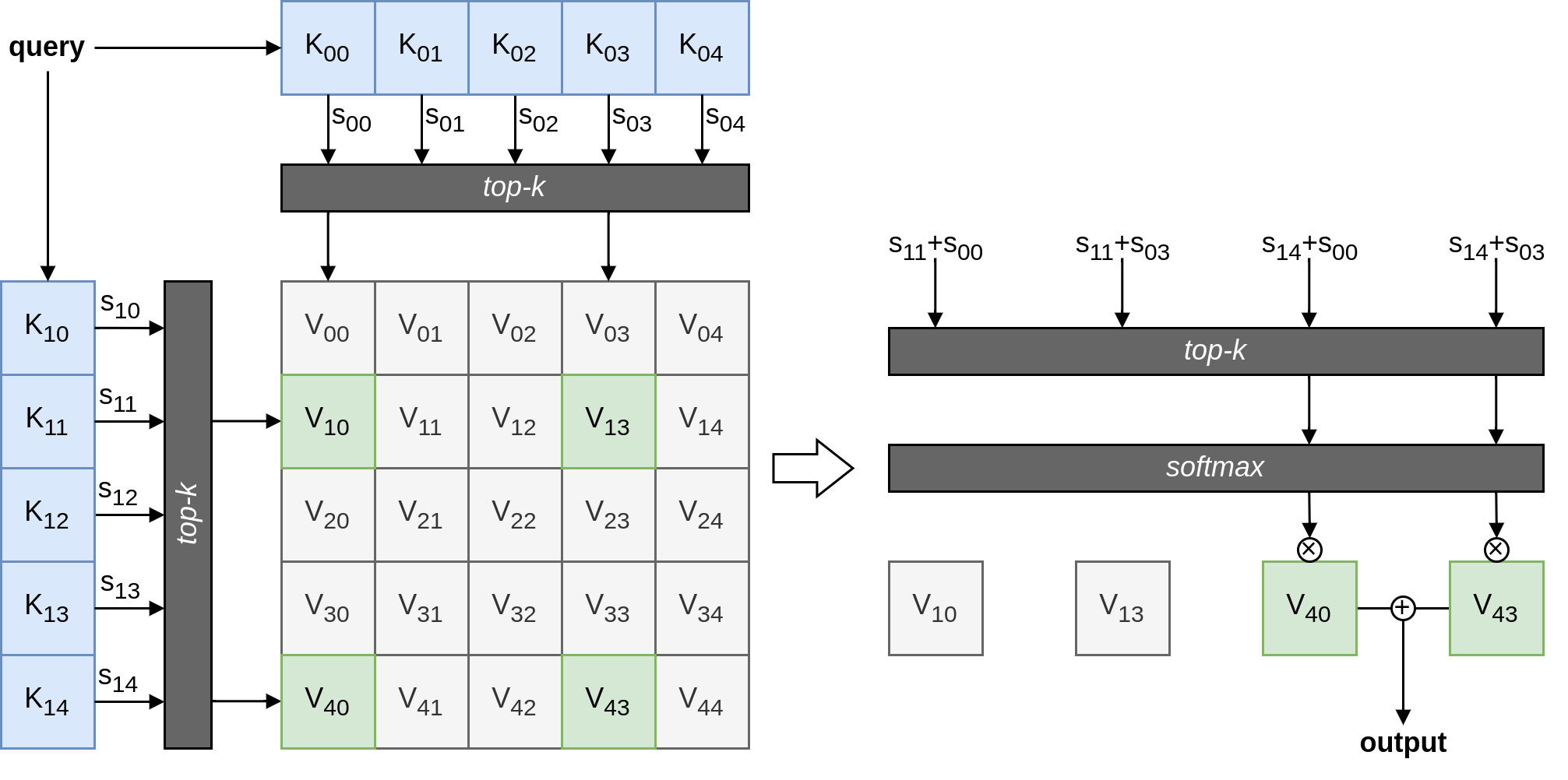

A memory layer resembles sparse multi-head attention, except that the keys and values are directly trainable parameters, rather than projections of an input activation. The process follows:

- Derive a query from the input via a small query MLP.

- For each head, compute scores via dot product of query with every key.

- Select the top-k scores.

- Softmax selected scores to get weights.

- Compute the weighted sum of selected values as the output.

Unfortunately, this design has a high compute cost as the memory size is increased, since the query-key dot product is exhaustive. This is remedied using product keys, which compute similarity against two distinct sets of keys $K_1$ and $K_2$ to give score vectors $s_1$ and $s_2$, then the score for a given value $V_{ij}$ is $s_{1i} + s_{2j}$. This means the amount of compute scales as $\sqrt{N}$ for memory size $N$. The process is illustrated in the figure above.

Their technique

This work makes a few architectural modifications to the product key memory layer to produce a Memory+ layer and trains it at scale in a modern Llama transformer architecture. The changes are:

- Wrap multi-head product key memory within a swiglu-gated MLP. The memory layer replaces the linear up-projection.

- Replace 3 MLP layers, equally spaced in the transformer stack, with memory layers, which have distinct query MLPs and keys, but shared memory values.

- Use a small key dimension. For hidden size $H$, the value dimension is set to $H$, while each product key is size $H/4$.

For example, the largest model they train is based on Llama 3, replacing 3 MLPs with product key memories with $2 \times 4096$ keys, so the number of memory items (shared between all memory layers) is $4096^2 = 16\textrm{M}$. Each value is a vector of size $4096$, so the number of memory parameters (which is dominated by values) is $4096^3 = 64\textrm{B}$.

Results

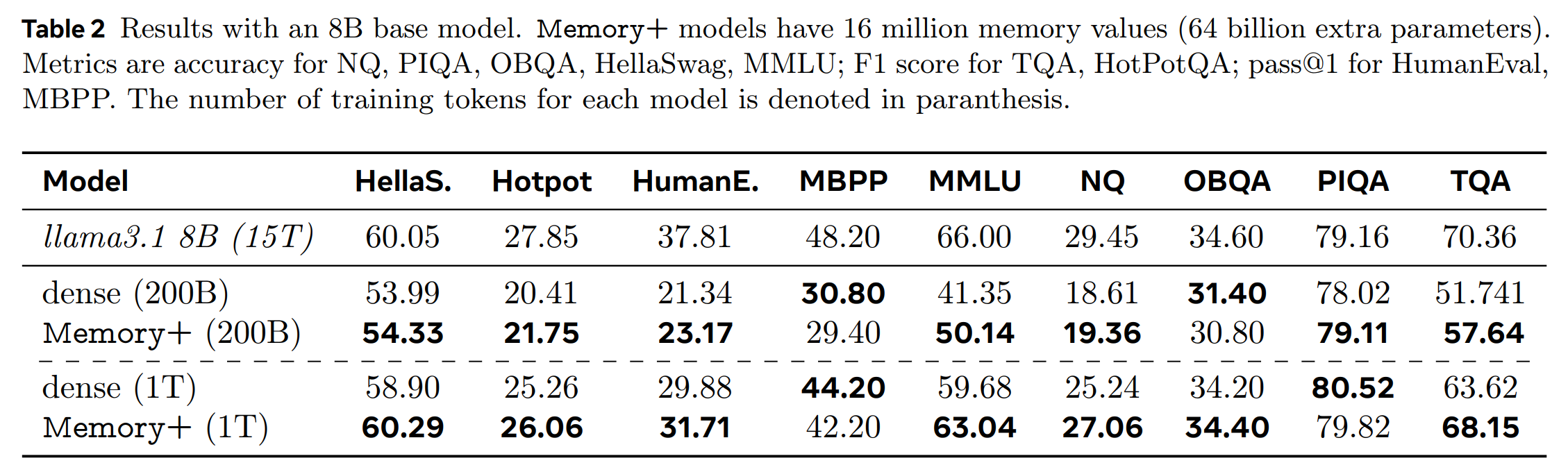

To test their architecture, the authors train autoregressive language models and evaluate multiple downstream tasks. They show improvements with training FLOP parity across models from 134M to 8B parameters, compared against mixture-of-expert models as well as dense models and vanilla product key memory layers.

Their headline result shows task performance improvement as the memory layer is scaled, allowing a 1.3B model with Memory+ layers to approach the performance of a 7B model without memory layers (dashed line).

Their largest model (8B) follows the Llama 3 architecture, and generally outperforms the dense baseline after 1T training tokens, although not consistently across all downstream tasks.

Takeaways

The work shows promise for product key memory layers at scale. As the authors note, gains are more pronounced in early training, so it will be important to confirm the benefit for inference-optimised overtrained LLMs. They also highlight the challenge of optimising and co-evolving sparse techniques such as this with ML hardware.

Comments