Mixture of a Million Experts

The key idea

Mixture-of-expert (MoE) layers are a popular choice for replacing burdensome MLP layers in Transformers. Standard approaches tend to stick to small expert counts (e.g., 8 or 16), as this permits straightforward, scalable implementation in tensor-parallelised distributed training settings. However, previous work suggests that a more compute-optimal configuration would be to use many small experts. In this work, the author designs an efficient routing strategy that allows them to test this hypothesis to the extreme.

Background

It is not immediately obvious why many small experts should be compute-optimal, however starting from a scaling law for MoE developed in previous work we see that test loss is expected to follow

$\mathcal{L} = c + \frac{g}{G^\gamma + a}\frac{1}{P^\alpha} + \frac{b}{D^\beta}$

where $P$ is the total number of parameters, $D$ is the number of training tokens, and $G$ is the number of active experts. $G$ is further defined as $G = P_{active}/P_{expert}$, i.e, the number of parameters used per token divided by the number of parameters per experts.

Ideally we want to keep $P_{active}$ small as this limits cost of transfers from main memory. However, we also want increase $G$ and $P$ since these will reduce test loss. To do this, we increase $P$ but decrease $P_{experts}$ according to a limited $P_{active}$. This implies employing many small experts rather than few large experts should result in a better trade-off for decreasing test loss.

Their method

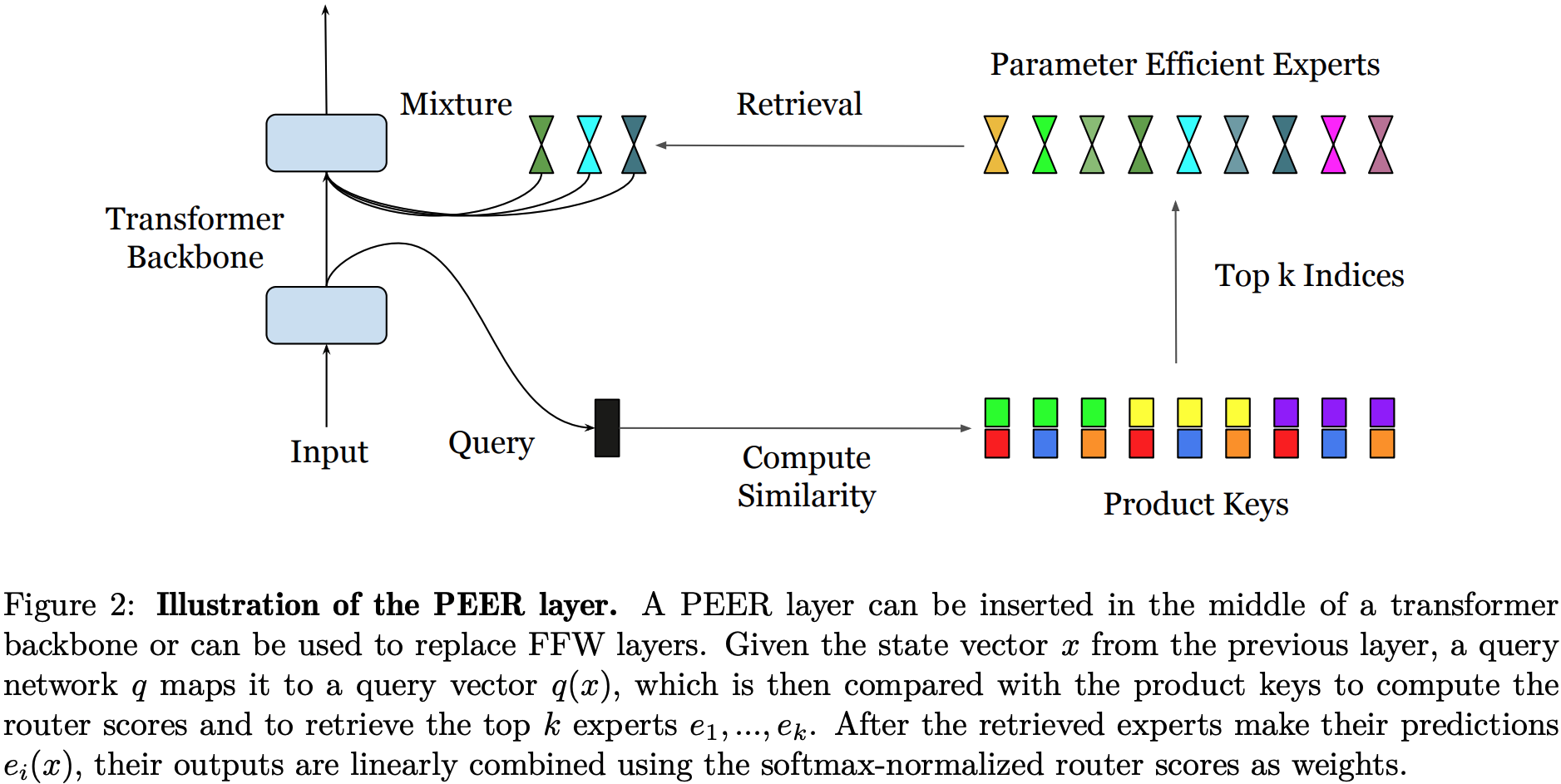

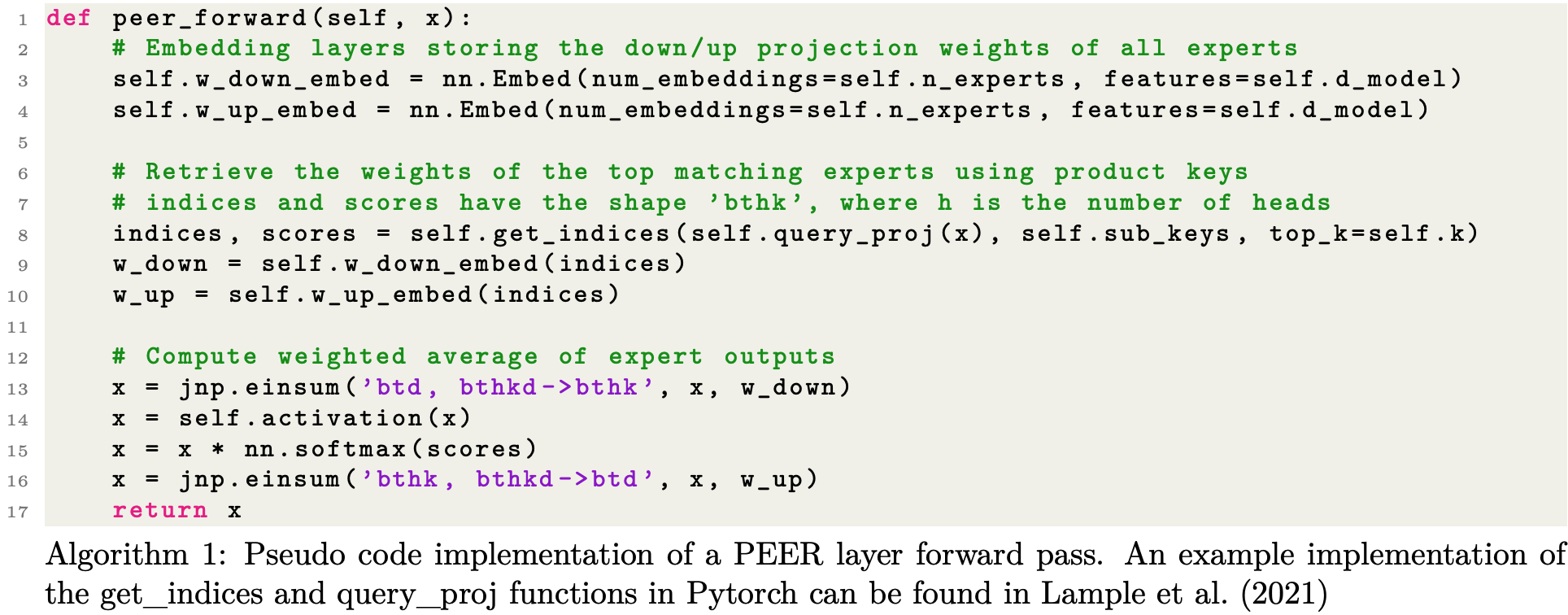

To actualise this idea, the author proposes the Parameter Efficient Expert Retrieval (PEER) layer. This design makes a few key choices:

- Experts are MLPs with a hidden size of 1 (Singleton MLP). This means $G$ is always as large as it can be for a given limit on $P_{active}$.

- Expert weights are constructed by concatenating weights from 2 “sub-experts”. This enforces a degree of parameter sharing across experts, but permits cheap retrieval from

2*sqrt(num_experts)rather than expensive retrieval from fullnum_experts. - Multi-headed structure used in previous work, in which inputs are projected to multiple queries, and each query retrieves many experts. Since outputs are summed across heads this is effectively like building an MLP from a larger pool of possible weights for each input.

Results

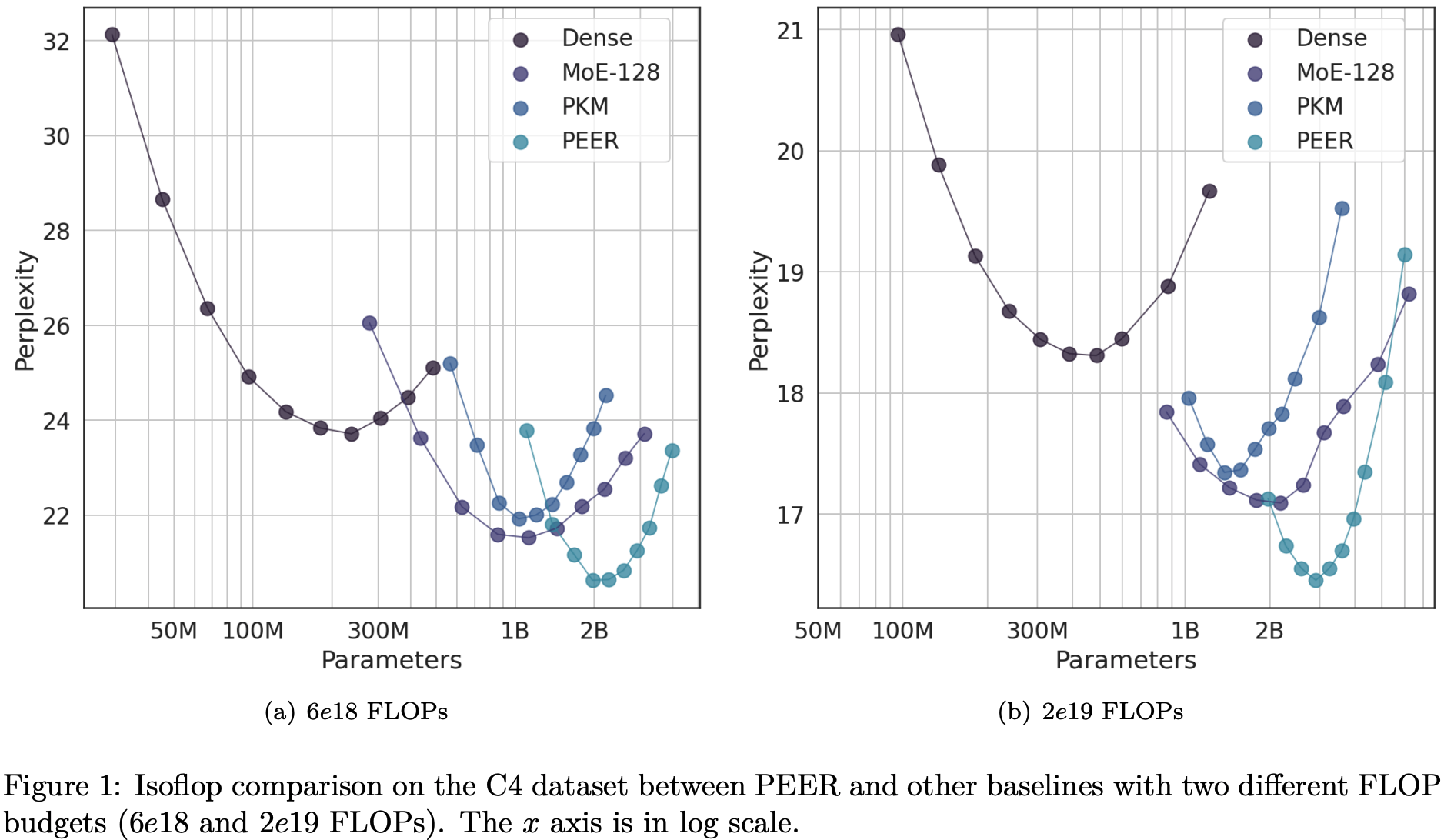

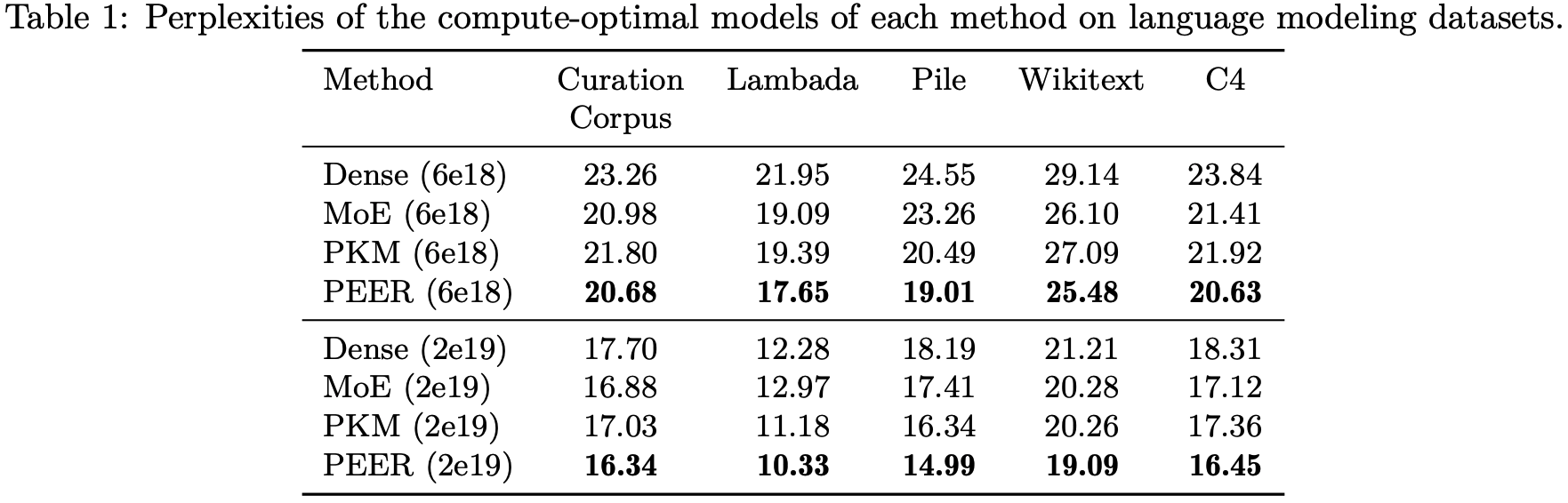

To characterise the compute trade-offs of using the PEER layer, the author uses iso-FLOP analysis in which total FLOPs are kept constant by trading training tokens for parameter counts. At first glance it looks like a clear win for PEER layers against dense baselines and other MoE architectures with smaller expert counts. The dense baseline looks a bit high for transformer architectures and datasets used in 2024 (would expect perplexity < 10 for 2e19 FLOPs), but appears to be consistent with the setup used for Chinchilla.

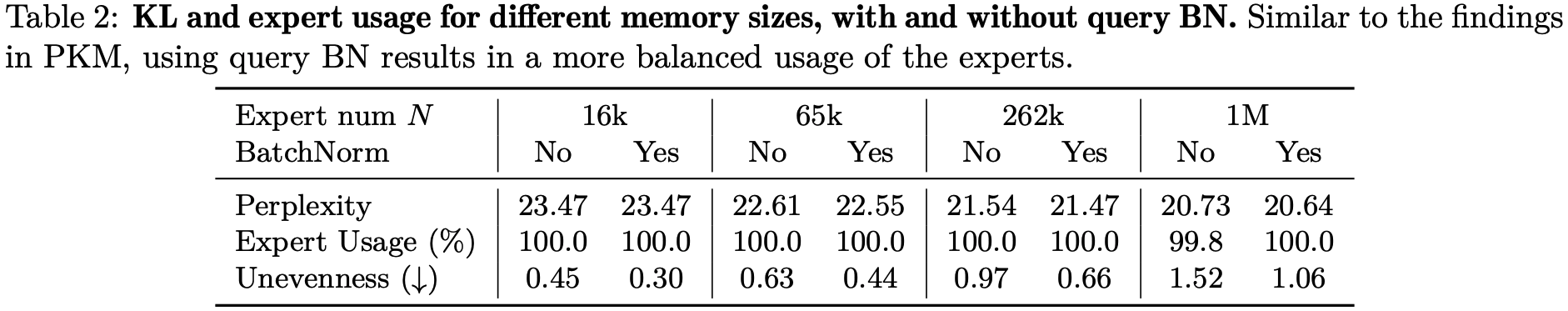

A common worry with using MoE layers is load-balancing across experts. A further concern as you increase the number of experts is whether some experts are being used at all. They show here though that expert usage is 100% (or near enough). There appear to be some issues with load balancing, but using batch normalisation over queries appears to help balance experts while actually improving test loss. This is useful to know given that regularisation strategies commonly used to encourage load balancing often harm test loss, but are needed to maintain higher throughput. I’m a little skeptical here as perplexity for this experiment is a fair bit higher. I’m guessing this is just because the author didn’t train for as long to perform ablation, but couldn’t see specific details.

Takeaway

This is an exciting line of work that has plenty of implications for how we attach memory to compute. While these results seem to be part of a work-in-progress, this is sufficient for me to want to try out in my own time and convince myself that these efficiencies are real and scaleable!

Comments