Scaling Exponents Across Parameterizations and Optimizers

The key idea

Our field has an insatiable desire to build ever-larger language models. From this, there’s an increasing need to predict how training will behave as model size is scaled up: How do we know that our hyperparameters chosen based on small models will continue to work on large ones? This work builds on the foundation of muP (Yang et al.) to explore parameter transfer as transformer model width increases.

Their method

The principle is to ensure that activations remain at a constant scale (RMS) as model width $n$ increases, at initialisation and during training. To do this, insert scaling factors to parameter initialisation, as a multiplier on the parameter and on the learning rate. I.e.

(Note: $A = n^{-a}$, $B = n^{-b}$, $C = n^{-c}$ from the paper.)

A parametrisation defines the scaling factors $A,B,C$ in terms of $n$. The paper investigates four parametrisations: Standard (STP), NTK, muP and Mean Field (MFP). However, they show that these fall into two classes that should behave similarly and propose a new orthogonal variation “full alignment” versus “no alignment”. This is shown in Table 1 and Figure 1 in the paper, but we can simplify it for this summary:

The key properties of a parametrisation are $A \cdot B$, since this defines the weight scale at initialisation and $A \cdot C$ (for Adam) which defines the size of an update. Expanding these based on Table 1, we get:

| Weight type | Parametrisations | Init $A \cdot B$ | Update $A \cdot C$ (Full align) |

Update $A \cdot C$ (No align) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Embedding | {STP, NTK, muP, MFP} | $1$ | $1$ | $1$ |

| Hidden | {STP, NTK, muP, MFP} | $1/\sqrt{n}$ | $1/n$ | $1/\sqrt{n}$ |

| Readout | {STP, NTK} | $1/\sqrt{n}$ | $1/n$ | $1/\sqrt{n}$ |

| Readout | {muP, MFP} | $1/n$ | $1/n$ | $1/\sqrt{n}$ |

The two classes {STP, NTK} and {muP, MFP} therefore differ in their readout initialisation, with the muP class claiming that this should be smaller than the STP class, as the model scales. This is because muP assumes alignment between the initial readout parameter values and the change in the readout layer input (i.e. the term $W’^{(0)} \Delta z$, where $z$ is the input to the readout layer), over training.

Considering another form of alignment, the authors explore two extremes of the alignment between parameter updates and layer inputs: “full alignment” which says $|\Delta W’ z|$ scales like $n \cdot |\Delta W’| \cdot |z|$ and “no alignment” which says it scales like $\sqrt{n} \cdot |\Delta W’| \cdot |z|$.

From the table above (and Table 1), assuming no alignment implies larger learning rates than full alignment, as model width is increased.

Results

The paper’s experiments on scaling language model transformers are expansive, so we can only give a quick overview of the highlights.

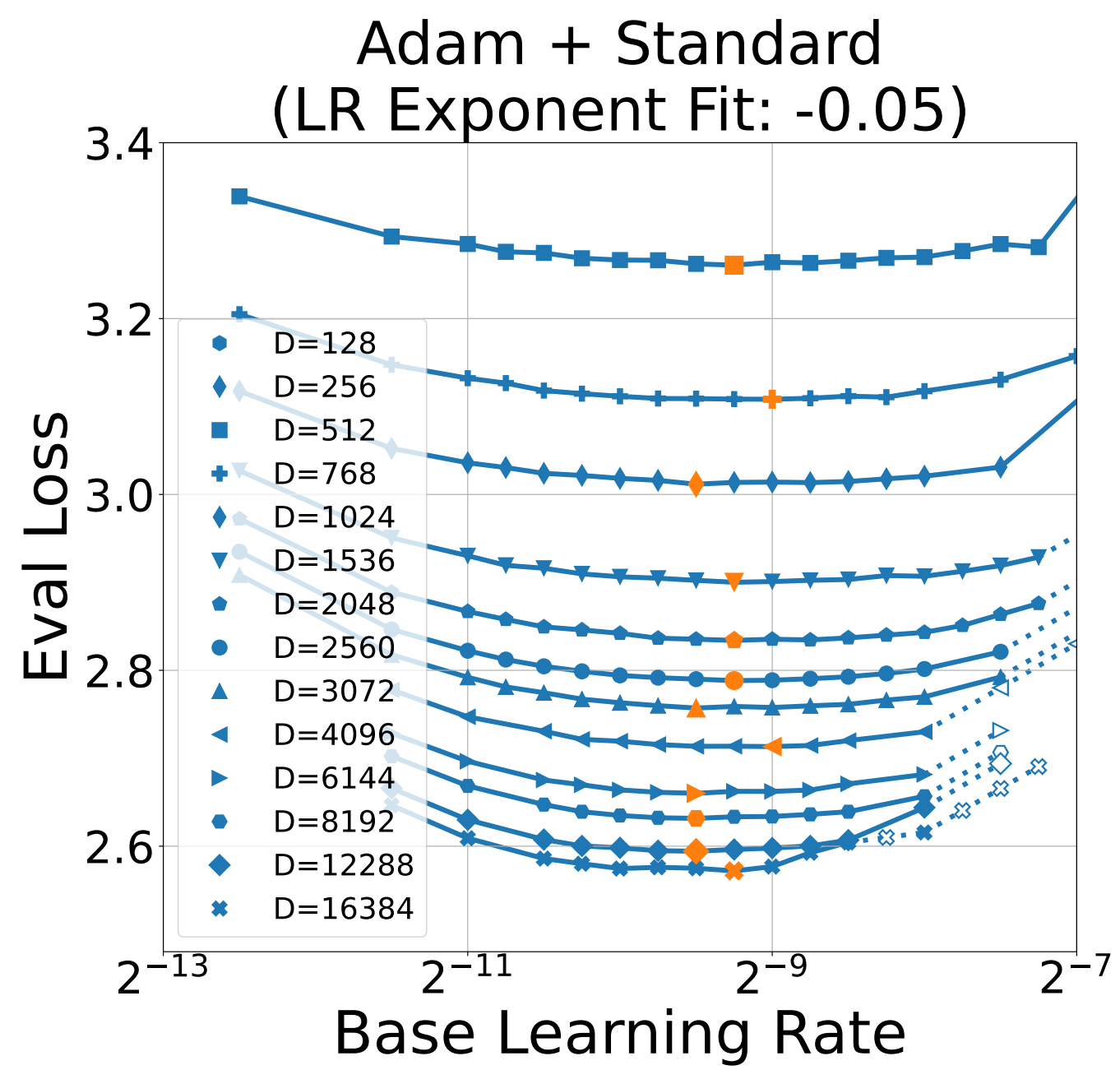

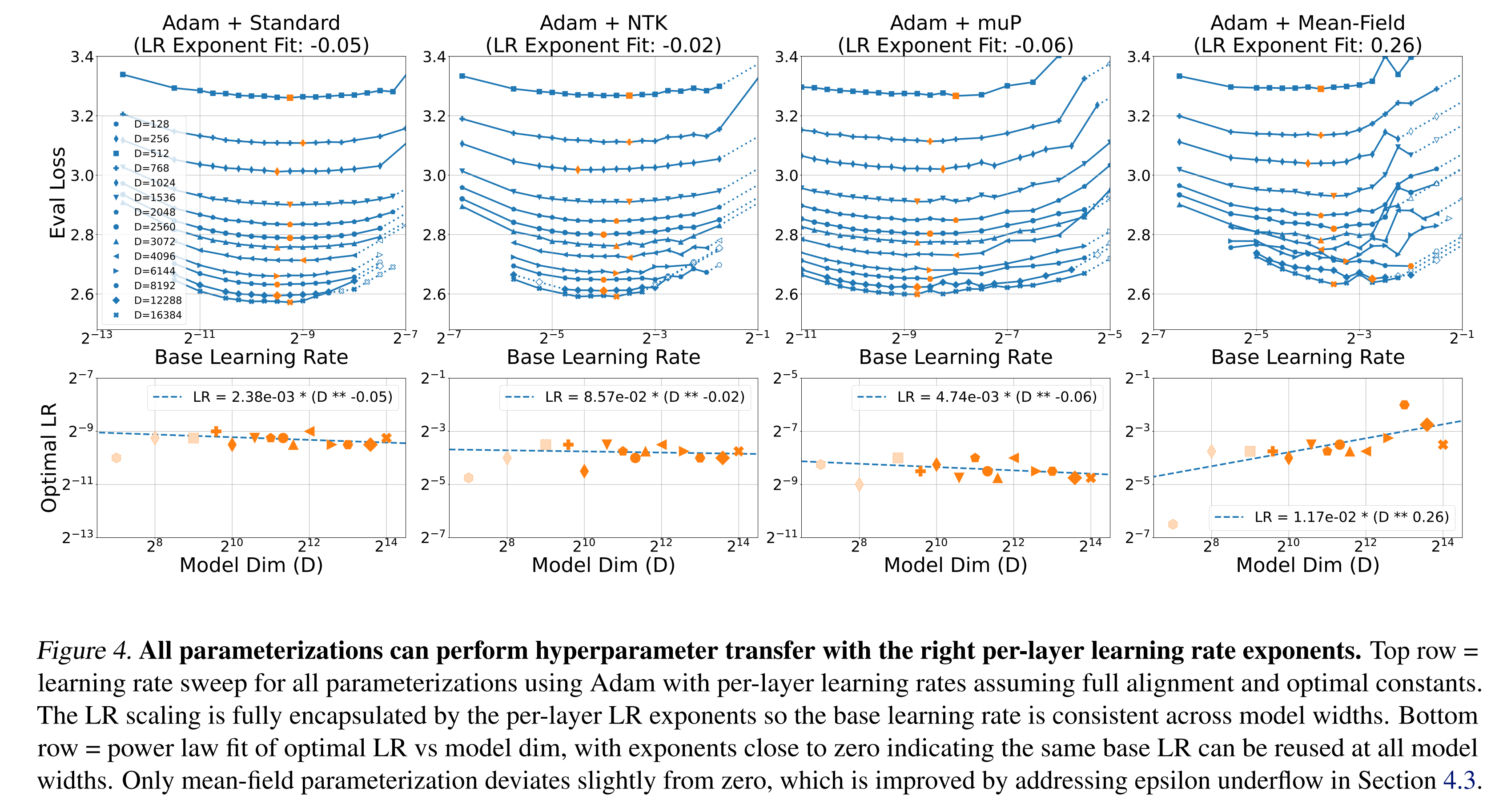

First, all parametrisations can give good LR transfer across width; under the full alignment assumption, when using Adam:

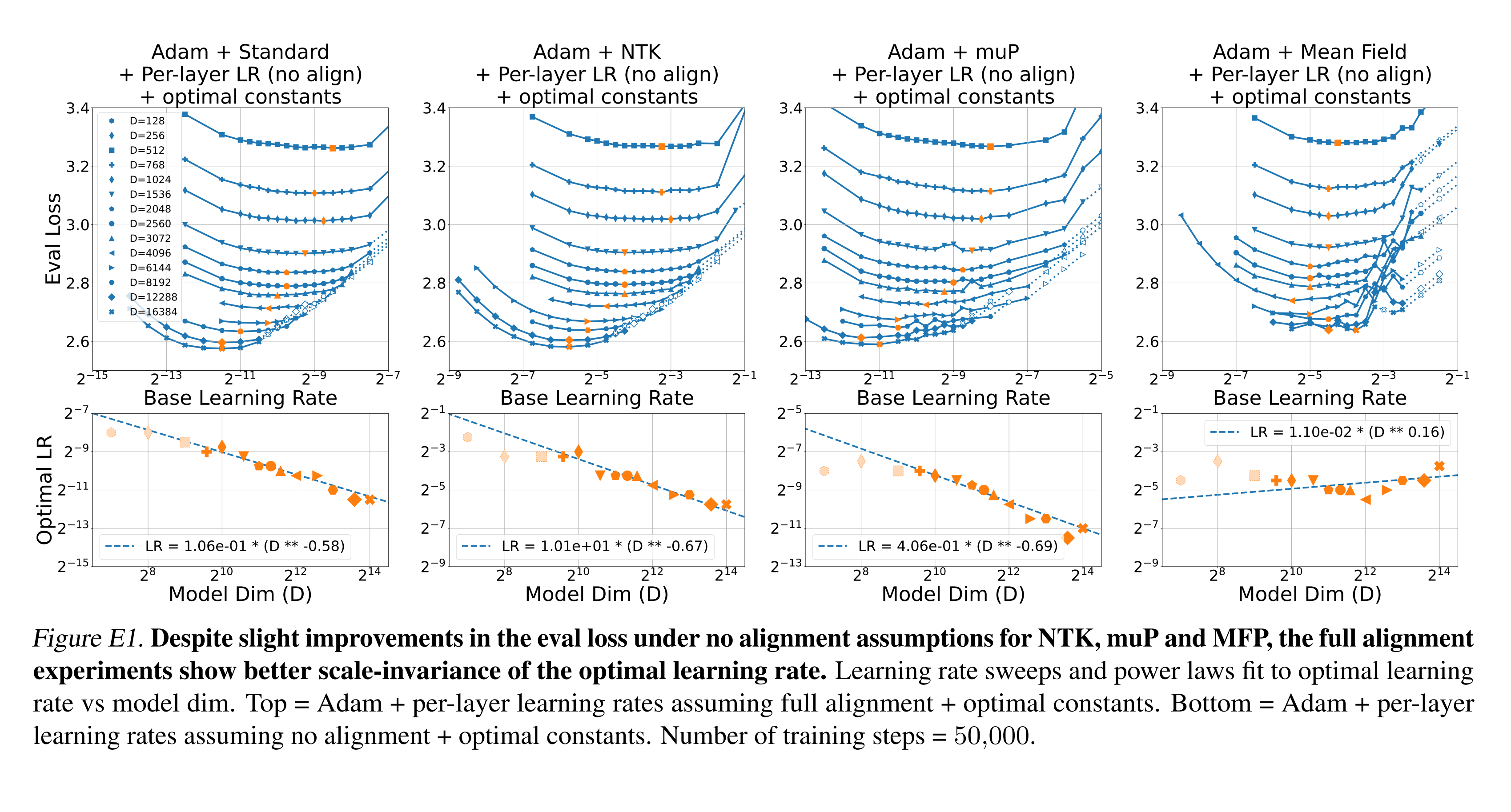

Compare this with the no alignment assumption, which doesn’t give good transfer with plain Adam:

However, their results when introducing parameter scaling (Appendix L), where the update is multiplied by the parameter magnitude, show a mixed picture. In this case, reasonable transfer is achieved with either full alignment or no alignment scaling.

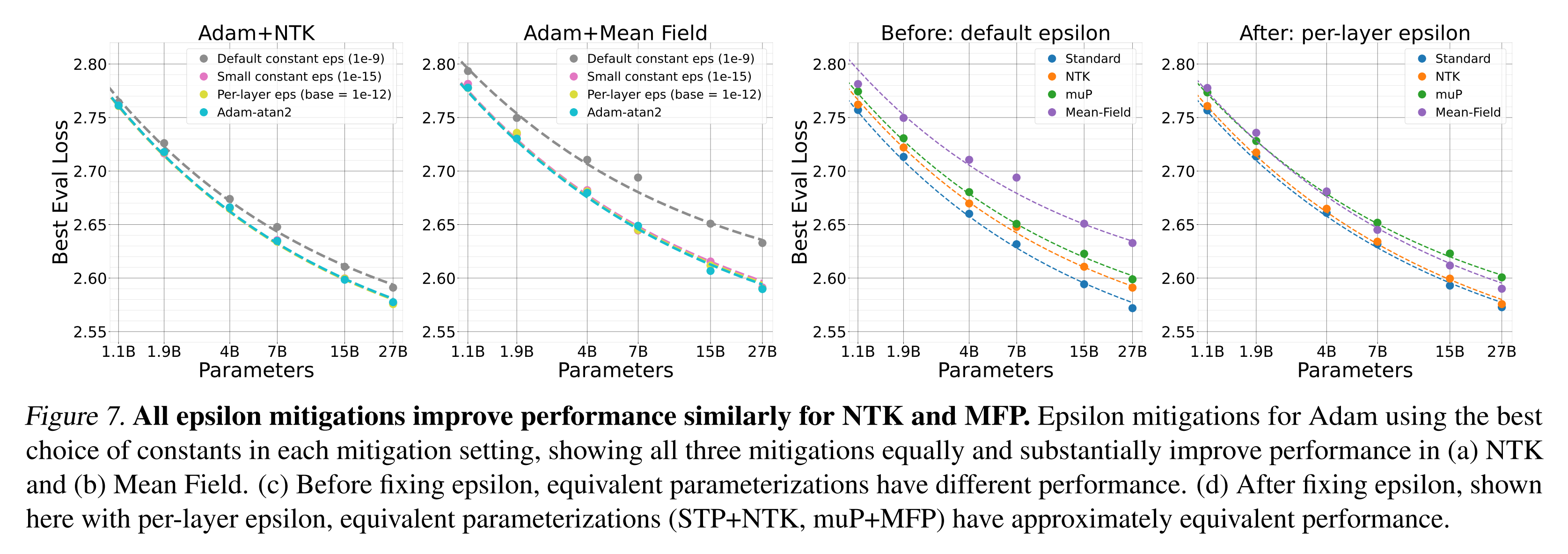

The experiments treat parametrisations separately, even though the theory has shown an equivalence in two classes. Since the authors identified that the Adam epsilon parameter is important (while it doesn’t factor into the scaling assumptions), they tried various schemes for fixing it, including a novel scheme where $m/\sqrt{v + \epsilon}$ is replaced with atan2(m, sqrt(v)). All schemes worked, fixing the visible scaling regression for NTK and MFP. They also made the results for two classes of (STP, NTK) and (muP, MFP) line up, which is very satisfying:

Takeaways

This work helps to clarify the similarities and differences between STP, NTK, muP and MFP (although the paper has simplified some, e.g. muP, to fit them into this framework). It has also highlighted where alignment assumptions are being made and questioned their validity.

The comprehensive experiments show that many factors can influence transfer results, such as parameter scaling in optimisers like Adafactor and the choice of Adam epsilon. Finally, the Adam-atan2 method is a neat way of working around the question of how to choose epsilon when the gradient scale varies.

Addendum

It’s impossible for me to avoid a comparison with our own experience of adapting muP in u-μP (Blake and Eichenberg, et al.), which shares the muP class w.r.t. readout scaling, but introduces a $1/\sqrt{n}$ scale to the embedding LR, unlike all of the schemes above. It is quite similar to MFP from this work, but unit-scaled μP avoids the poor gradient scaling that MFP experiences, by allowing gradients to be scaled independently from activations. Otherwise, our work pursued a different objective, removing the base width and coupled hyperparameters of muP.

Comments