The Era of 1-bit LLMs: All Large Language Models are in 1.58 Bits

The key idea

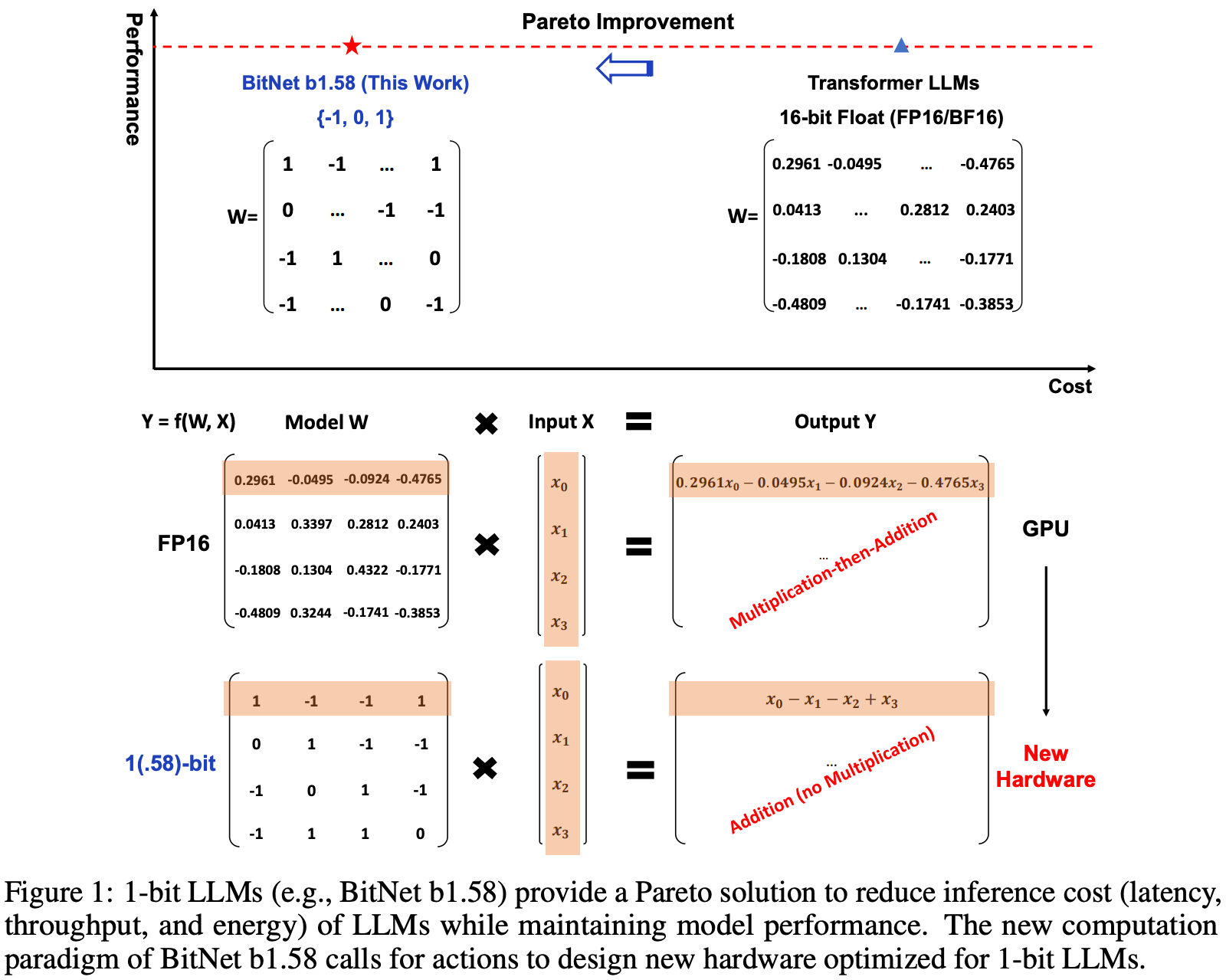

Training and inference of large language models when quantising weights to {-1, 0, 1} and activations to int8 during forward pass matrix multiplications performs similarly to FP16.

Their method

Master weights are stored in higher precision (e.g., FP16). With ZeRO-offloading, the memory overhead of these weights can be partly discounted and quantised weights can be computed once across gradient accumulation steps.

In the forward pass, linear layer weights are quantised to {-1, 0, 1} by normalising with the absolute mean, rounding to the nearest integer and clipping values outside this range. Activations are quantised to int8 by bucketing values with a simple absolute max rule.

Straight-through-estimators are used to compute gradients and are accumulated in FP16.

By restricting weight values to {-1, 0, 1}, matrix multiplications can be computed with cheap integer addition/subtraction instructions only, and without any need for expensive floating point fused multiply-accumulate (FMAC) instructions. In practice, the authors still use FP16 FMAC instructions in their implementation, perhaps to avoid costly casts and the need to compute non-matmul operations in higher precision.

Results

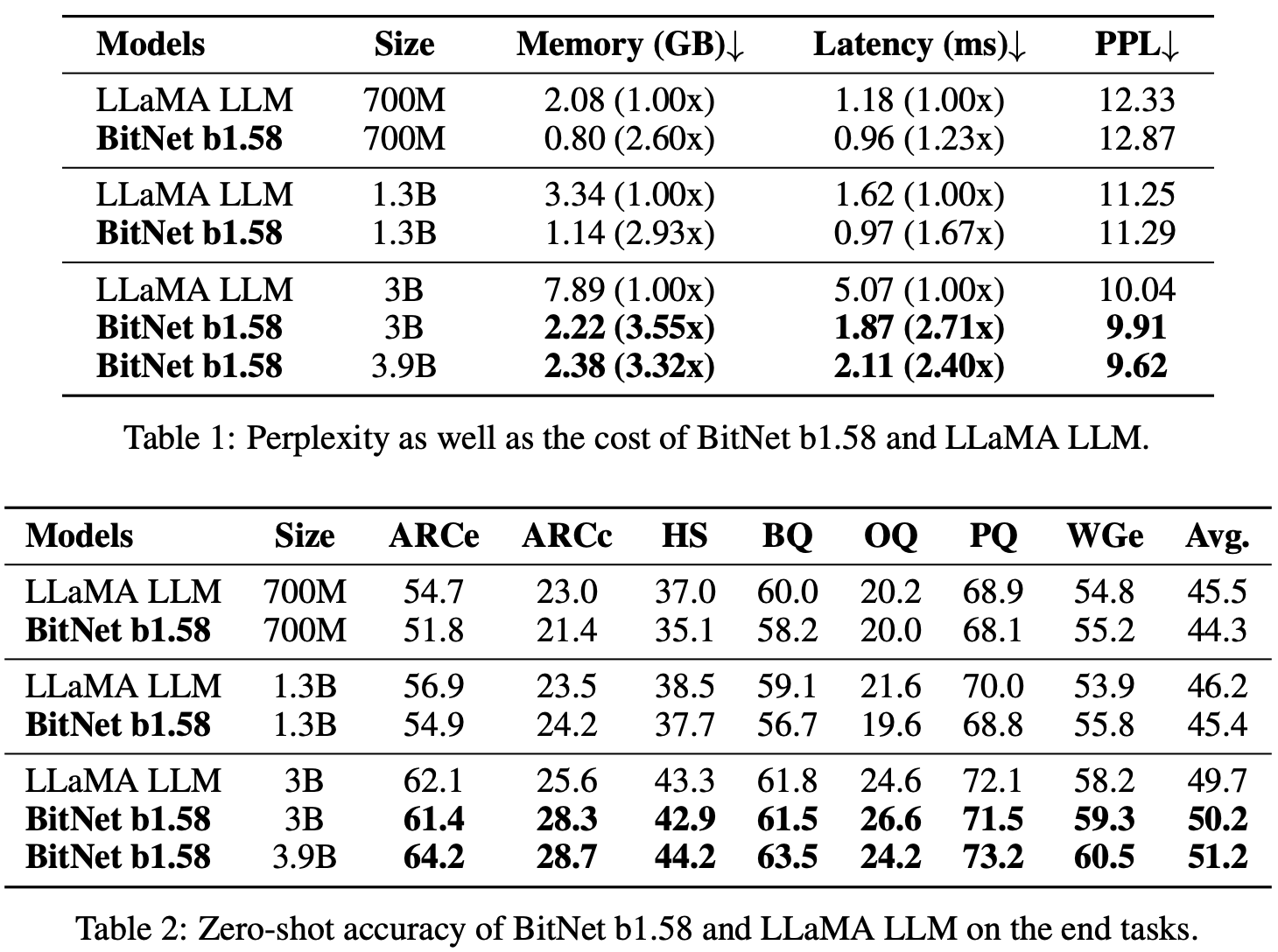

Comparing against FP16 Llama 3B pretrained on 100B tokens shows minimal change in validation perplexity and downstream task accuracy

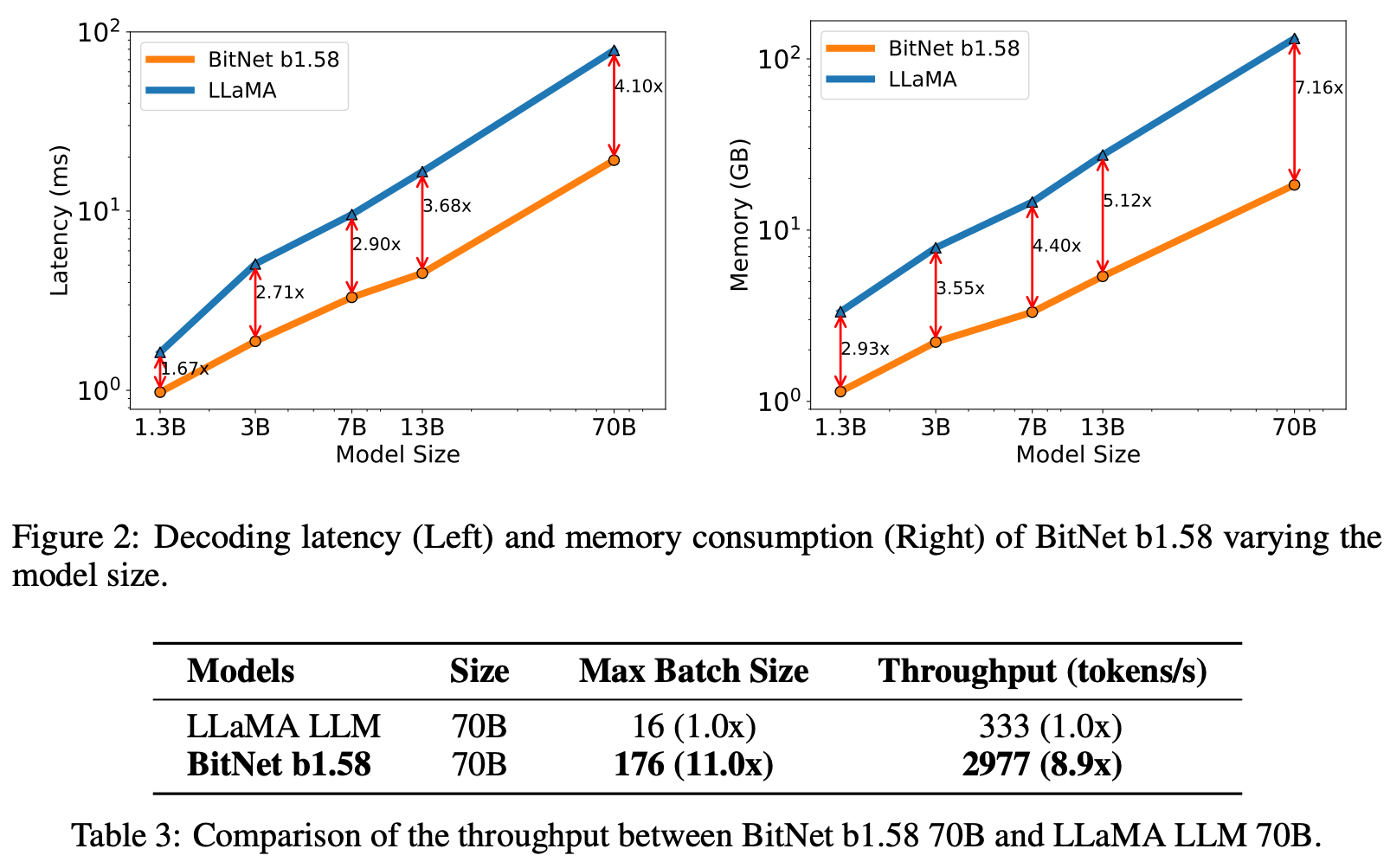

Even more impressively, 1.58-Bit LLM exceeds the performance StableLM-3B when reproducing training recipe on 2 trillion tokens.

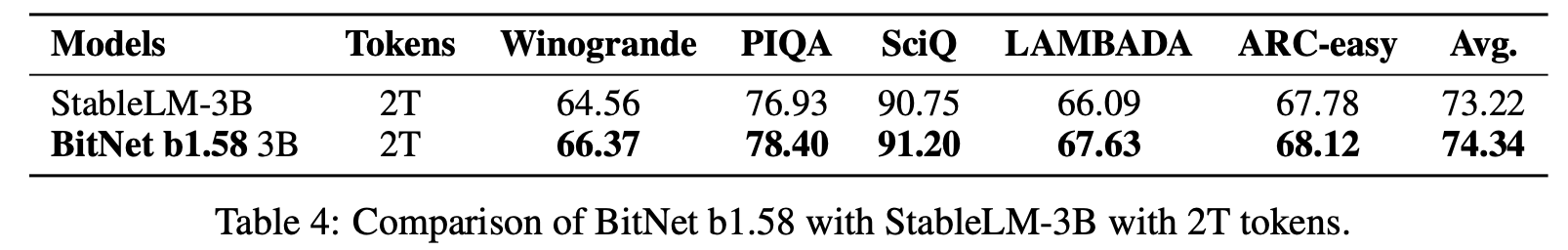

The authors also show latency and throughput improvements for LLM inference, mainly due to far smaller memory footprint of weights (1.58 bits per element) and KV-cache (8 bits per element). This is somewhat hard to compare since post-training quantisation to 2-bits can work really well but isn’t considered in this work.

Takeaways

At first glance, this is a “too good to be true” type result. However, some of these results have since been independently reproduced. It goes to show that matrix multiplications can be approximated with even looser bounds than is standard, while still producing smooth enough gradient signals for updating master weights.

The authors propose that new hardware could or should be designed to exploit the power-efficiency, theoretical speedup and memory savings of training without floating point multiply-accumulate units. This is a tantalising proposition, but should not be totally discounted against the cost of accumulators, reductions, casts, and elementwise functions in the design of specialised hardware.

Comments