xLSTM: Extended Long Short-Term Memory

The key idea

Recurrent neural networks based on Long Short-Term Memory units were the backbone of NLP models before the advent of the now-ubiquitous transformer. This work seeks to close the gap between LSTM and transformer in the crucial model-scaling regime of LLMs. They do this by extending the LSTM in two ways to create sLSTM and mLSTM, then incorporating these layers into a deep residual architecture, called xLSTM.

Their method

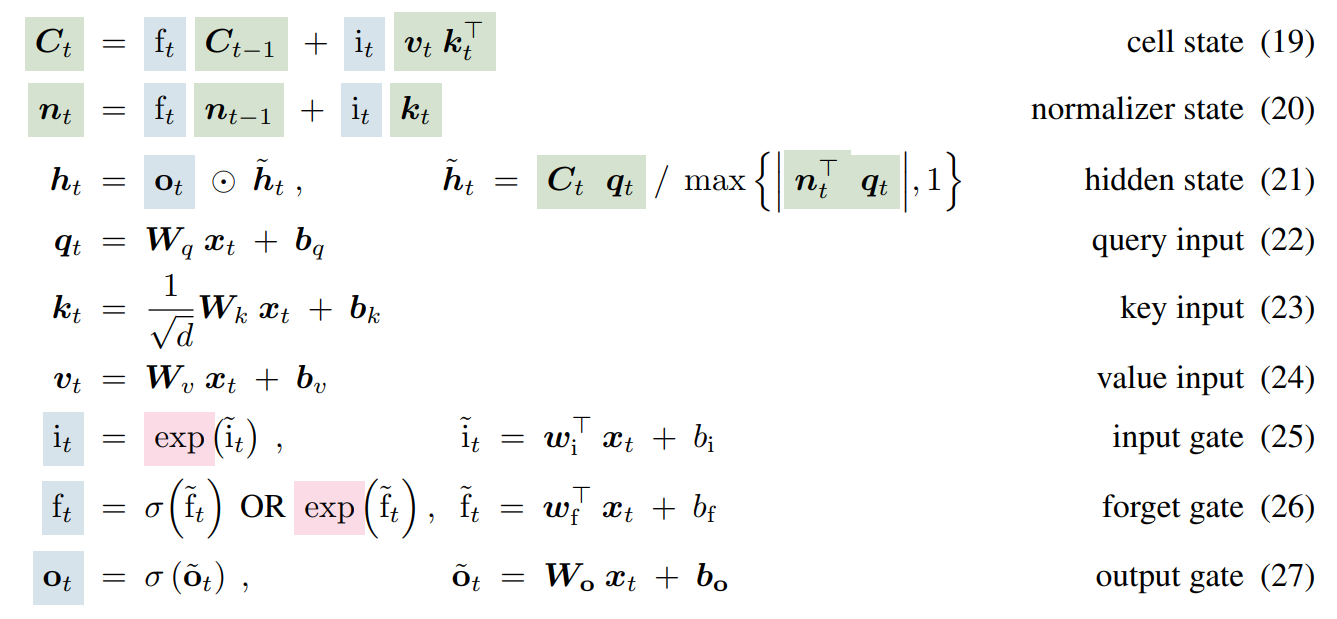

We’ll focus on the mLSTM variant, as the sLSTM variant is omitted from many of the best-performing models in their results. I think the best way to understand the architecture is to stare at a wall of maths for a while:

To give an intuition for this, there’s:

- Inputs $\mathbf{x}$ and parameters $\mathbf{W_{q,k,v,o}}$, $\mathbf{b_{q,k,v,o}}$, $\mathbf{w_{i,f}}$, $\mathbf{b_{i,f}}$.

- Six linear + activation ops, depending only on the inputs: $\textbf{q}, \textbf{k}, \textbf{v}, i, f, \textbf{o}$. The $f$ (forget) and $\textbf{o}$ (output) gates have sigmoid activation, giving outputs in the range $[0, 1]$, but $i$ (input) has an exponential activation. $\textbf{q}, \textbf{k}, \textbf{v}$ are linear.

- A “cell” $\textbf{C}$: a decayed and weighted sum of $\textbf{v} \textbf{k}^\top$ (which I’ll call KV mapping) over time. At each step, the state is decayed according to the forget gate $f$ and the KV mapping is weighted according to the input gate $i$. The cell maps queries to values by matching them against keys.

- A normalizer $\textbf{n}$: similar, but sums just $\textbf{k}$ instead of KV mapping.

- An output $\textbf{o}$, the inner product of query $\textbf{q}$ and cell, divided by the magnitude of the inner product of $\textbf{q}$ and normaliser, and multiplied by the output gate.

Like softmax dot product self-attention, this involves a normalised sum of exponentials; a key difference is that the input to exp depends only on the “source” (key, value), not on the “target” (query). It bears some similarities to linear attention, Mamba and RWKV, permitting a parallel scan over the inputs since time dependency is linear. It retains the RNN’s advantage of summarising the context in a fixed-size representation, $\textbf{C}$, for efficient autoregressive inference.

In the xLSTM architecture, this is used in a custom residual block that performs positionwise up projection before the multi-headed mLSTM.

Results

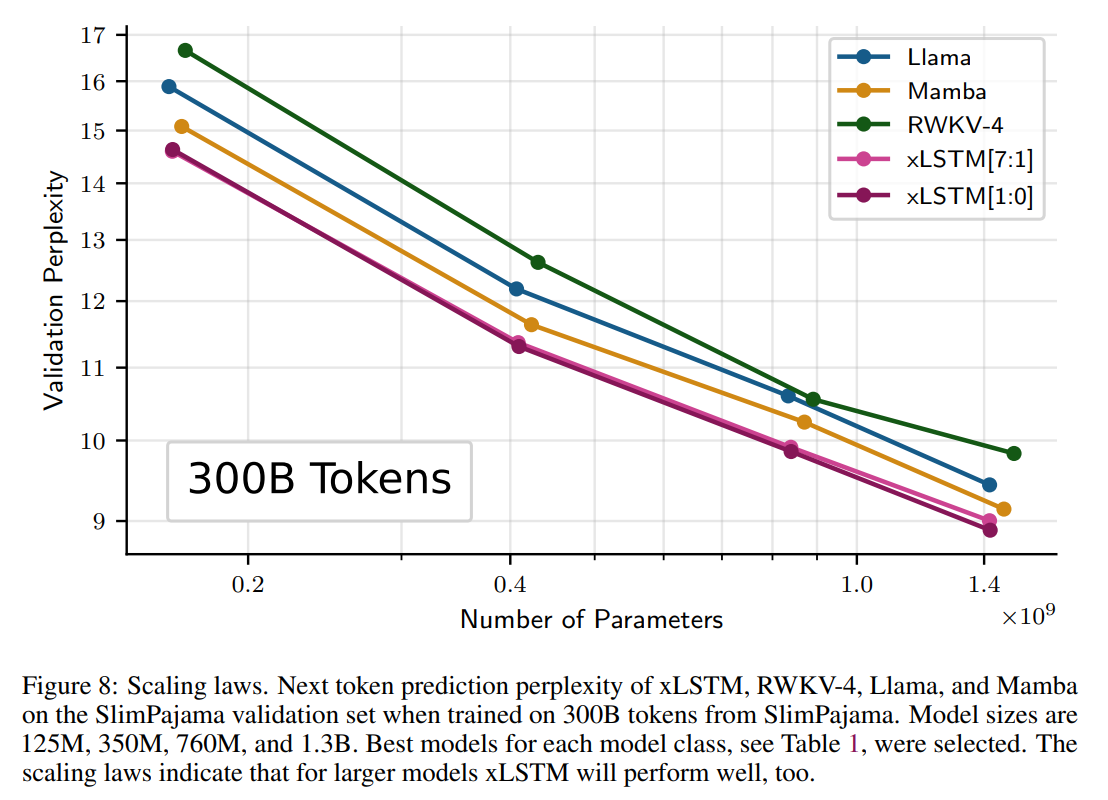

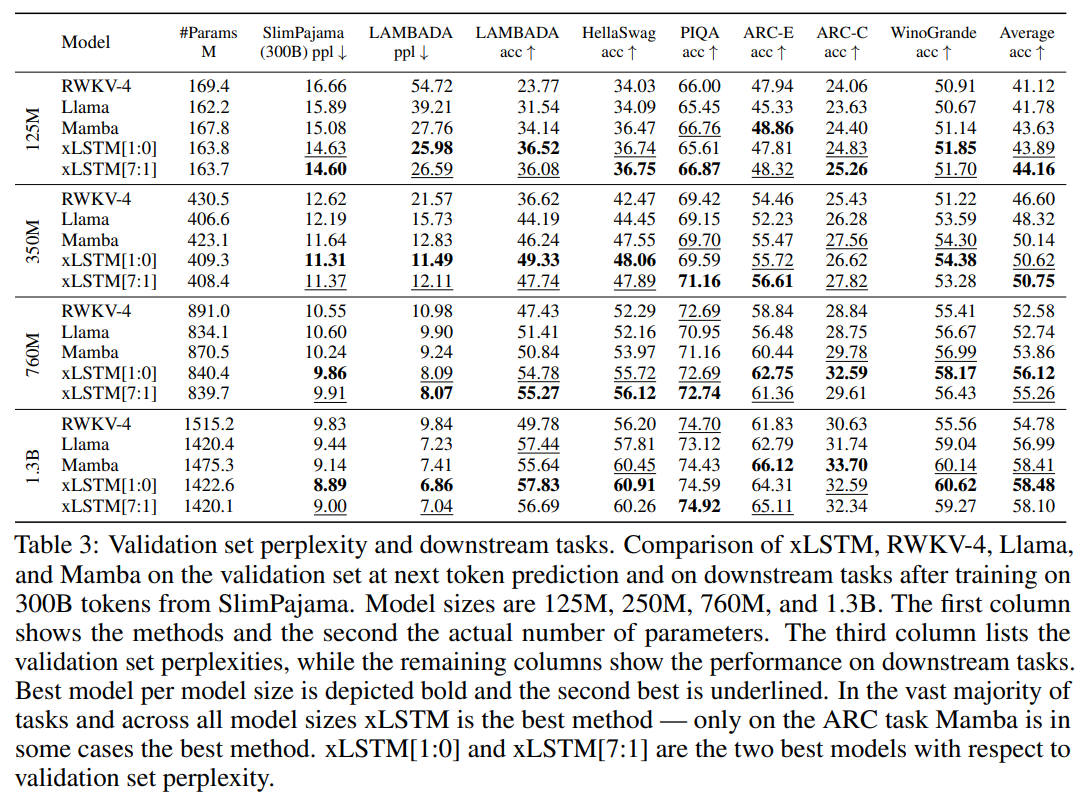

Downstream results for LLMs of up to 1.3B parameters, trained on 300B SlimPajama tokens:

(I haven’t been able to confirm if these are zero-shot or few-shot results.) Here, xLSTM[1:0] uses only the mLSTM layer described above, while xLSTM[7:1] includes 7 mLSTM layers per 1 sLSTM layer. These results appear to demonstrate the sufficiency of mLSTM for LLMs. The paper also includes a helpful set of ablations and synthetic tasks.

Takeaways

It’s refreshing to see non-transformer LLMs trained at scale, and that the xLSTM architecture appears competitive with transformers. More research could help us understand the benefits of these alternatives, and whether the scaling properties are robust.

Comments